At a glance

In a hurry? Read our summary of all the findings, evidence and data on child health outcomes across the UK as of early 2020. We provide a snapshot of physical and mental health, as well as the wider determinants of health.

State of Child Health 2020 provides an updated snapshot of children and young people’s health across the UK, aggregating comparable data across the four nations. It covers physical and mental health – and the wider determinants of health such as poverty, housing, and education.

In 2017, State of Child Health was the first report to highlight the health and wellbeing of children and young people across the four nations of the UK. The 2020 edition has new indicators – including the health of looked after children, mental health, injuries from physical violence and an overview of the child health workforce – to reflect changing trends, priorities and evolving challenges.

Collating updated data on children and young people’s health allows us to track progress across the four nations in relative and absolute terms. By providing a lens through which to focus on the areas of greatest need, the report will assist policymakers to prioritise and practitioners to strengthen their practice.

The findings in this report may make uncomfortable reading, but the message is vital. As adults our first and primary responsibility is to give children and young people the best possible start in life, and a hand up if that start is tough. It’s time now to deliver – it will cost money and energy - but it will be returned to all of us many times over. Our children deserve nothing less.

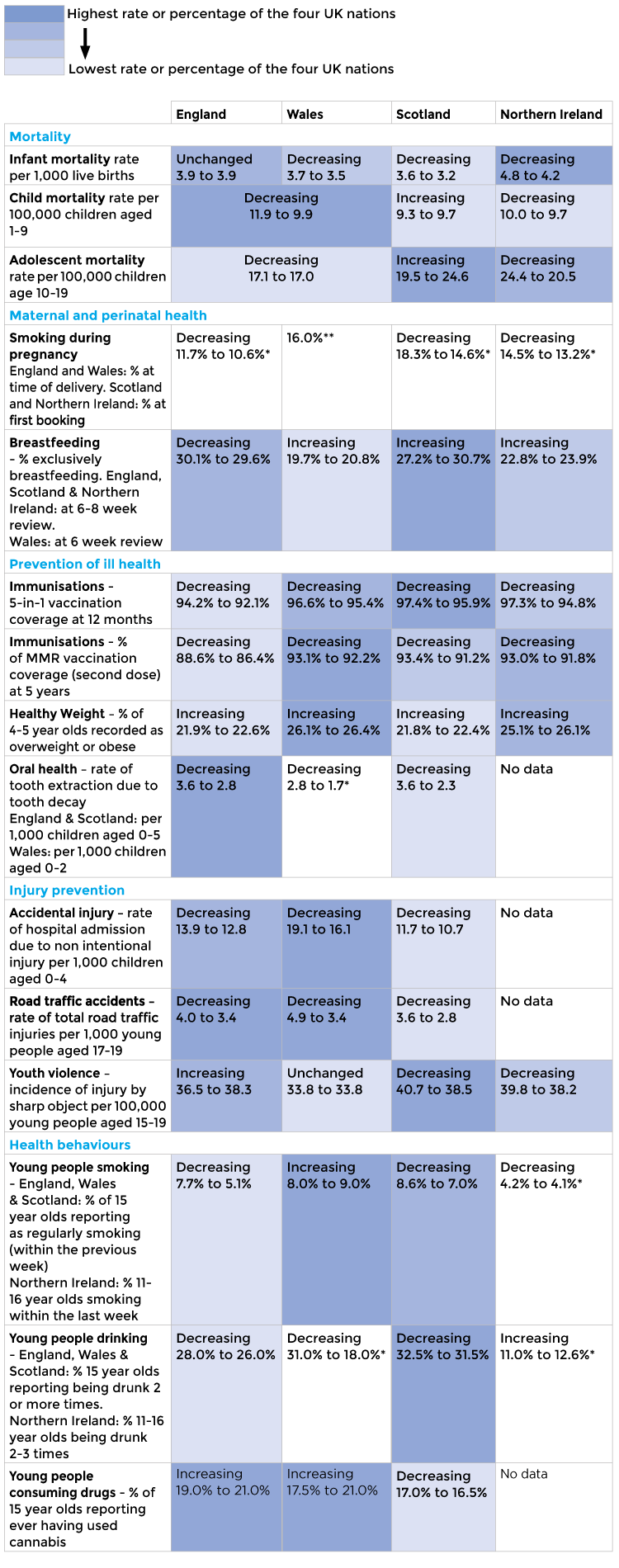

Progress on indicators – 2014 to early 2020

For each of our State of Child Health indicators, we have identified whether the trend is increasing, decreasing or unchanged. Trends reflect available data that was included in the State of Child Health 2017, typically 2014 data, compared to data available as of 21 February 2020.

A summary of the findings is shown here. To note, the colour coding is only shown where there is directly comparable data across all four nations.

Areas of improvement

Some indicators have improved since the last report in 2017. There has been continued improvement in blood glucose control among children and young people with Type 1 diabetes across England and Wales, and it is encouraging that there have been increases in the completion of key health checks for those with diabetes. In England, rates of emergency admission to hospital for epilepsy have fallen among those living in the most deprived areas, across all age groups. These are welcome examples of how clinically driven national improvement initiatives, supported by investment in high quality data collection and a robust network of care, can reduce health inequalities and yield tangible improvements in outcomes.

There have been many notable public health achievements – and it is no accident that progress is greatest in areas where policymakers and practitioners have coalesced around a coherent, persuasive, system-wide national strategy. The rate of conceptions among those aged under 18 years has also consistently been decreasing over the past decade in England, Scotland and Wales – with trends in livebirths to teenage mothers in Northern Ireland (the closest alternative available indicator) reflecting a similar picture. Oral health in young children continues to improve, particularly in Scotland and Wales, where prominent, well-executed national strategies implemented a decade ago continue to have positive effects.

Progress is stalling, or reversing, in important areas

In areas of improvement, including emergency hospital admissions for long term conditions and teenage conception/births, we still fall behind comparable high income countries in Europe and beyond.

The report also highlights areas where progress has stalled, and in some cases where things are getting worse.

It is the indicators that rely on a robust public health mechanism where problems are most apparent. Progress in reducing child and adolescent mortality has stalled in recent years. Of greater concern still is the lack of progress in infant mortality in England from 2013 to 2018, with a slight rise seen in 2017 – a measure which acts as a bellwether for the overall health of the nation.

Progress in reducing smoking during pregnancy has stalled, and in Scotland the proportion of women who reported smoking at the first health visitor review has actually increased since the last report. Tackling obesity continues to be a challenge with 34% of children and young people aged 10-11 in England being overweight or obese. Uptake of early vaccinations has universally fallen, for both the MMR and 5-in-1 vaccines, and across all four nations with England and Wales recently losing its WHO measles free status.

Arresting the decline in all these areas relies upon a renewed, well-resourced focus on prevention and health promotion, and safeguarding the high-quality provision of universal health services.

Inequality persists

Inequality continues to blight the lives of children and young people in the UK and is a recurring theme across several of the indicators across the report.

Child poverty has increased for those in working families. Inequalities in some health outcomes have widened since the last report: infant mortality in England has risen particularly for those living in the poorest areas, for instance, and inequalities in obesity in England at age 10-11 have also widened.

New indicators for 2020 report

Among the new indicators, it is worth noting the prevalence of mental health disorders in England. This shows increases in emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression for those aged 5 to 15 years and a particularly high (23%) prevalence of emotional disorders among young women aged 17-19. The dearth of comparable information in other nations remains a source of frustration.

The child health workforce, too, illustrates areas where a mismatch between rising demand and shrinking resources is reaching tipping point. Recruitment of paediatric doctors has increased – but not enough to keep pace with demand and retention challenges. Meanwhile, nursing increases have primarily come in the acute sector, at the expense of health visiting and community nursing. Mental health services, too, show disparities between the four nations.

Policy progress

Central to the report are the policy recommendations for Government, policymakers and decision-makers on how to address the deficits. Ambitious as the previous report’s recommendations were, we have seen the influence they had on Government and other stakeholders in shaping child health policy in the intervening years.

But, as the data trends outlined above can attest, much work remains.

We’ve developed country-specific policy recommendations in 2020, which call on stakeholders to transform commitments into action.

Key recommendations

Each of the report’s indicators include specific recommendations which, we believe, will lead to improvements in outcomes for children and young people.

However, specific actions relating only to specific populations, certain diseases or public health issues will not be enough. Taking the totality of the data findings, it is clear that child health in the UK must be urgently prioritised, which can be achieved by attending to three crucial, overarching issues:

Reduce child health inequalities Action should be taken to tackle the causes of poverty and reduce variation in outcomes.

Read morePrioritise public health, prevention and early intervention Preventative measures will reverse current trends and ensure healthy children become healthy adults.

Read moreBuild and strengthen local, cross-sector services There should be equitable access to services, resources, advice and support within the local community.

Read moreThe progress being made in these three areas will vary between each nation. We have therefore made individual policy recommendations for each of the four nations, outlining specific policies and approaches by which each of the nations should bolster their national child health system.

To achieve these goals, complementing nation-specific recommendations with a broader, UK-wide approach is critical; we continue to advocate for children and young people’s health to be at the forefront of decision-making, through adoption of a ‘child health in all policies’ approach to policy development.

The role of health professionals

To those working in clinical practice, reports like State of Child Health can sometimes feel remote and inaccessible, with national trends and policy recommendations seemingly disconnected to those who deliver care. But improving child health at a national level is not just a matter for Government or policymakers. We want to make this updated version of the report relevant for health professionals, and to this end, each of the indicators has practice-related tips and resources.

Just as there are overarching, unifying themes to be tackled from a policy perspective, so too there are tips for practitioners that are applicable across the indicators:

- Making every contact count

- Signpost disadvantaged children, young people and their families to sources of support

- Advocate for local children, young people and their families

- Take an active role in supporting child health research and data collection

- Make child health a joyful place to work

How you can help

Like and share our #StateofChildHealth content on your social networks. Search the hashtag or click through to our Twitter and Facebook accounts.

Email your MP and ask them what they’re doing to prioritise child health. You can find your MP here.

Authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

Published March 2020

Explore the evidence

-

Mortality

Mortality rates are an important marker of the overall health of society. Explore the evidence for mortality in infants, and children aged 1-9 and 10-19 years across the UK.

Read more

-

Maternal and perinatal health

Maximising maternal health and wellbeing during and after pregnancy improves child health outcomes, including stopping smoking and breastfeeding.

Read more

-

Prevention of ill health

Prevention and early intervention in childhood foster healthy behaviours throughout life, especially for improvements in immunisation take up, healthy weight and oral health.

Read more

-

Injury prevention

Accidents happen throughout childhood and adolescence, from non-intentional injuries in under-fives to injuries from road traffic accidents and physical violence in young people. These can be prevented with interventions and safety measures.

Read more

-

Health behaviours

Young people who experiment with smoking, alcohol and drugs are more likely to continue these habits into later life, with impacts on their physical and mental health. We also look at conception rates in teenage women.

Read more

-

Mental health

Early intervention in mental health and wellbeing is key; prevalence of mental health conditions and suicide rates are increasing and mental health services must be equipped to meet growing demand.

Read more

-

Family and social environment

A number of social determinants impact on a child’s health outcomes, including poverty, education, the health of their family and whether they require targeted support from social services (such as Looked After Children).

Read more

-

Long term conditions

Many long term conditions develop during childhood; these children are more likely to develop mental health conditions and should be supported to navigate the transition from child to adult health services. We look at asthma, epilepsy diabetes, cancer and disability / additional learning needs.

Read more

-

Workforce

A child health workforce of sufficient number and skill is crucial to efforts to improve the health of children and young people in the UK. Currently, demand for child health services outstrips capacity.

Read more