Oral health

Dental extractions remain a top reason children in the UK require hospital admission. Tooth decay can be prevented with changes to diet and good oral health habits.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- Poor oral health can lead to:1, 2

- Pain

- Infections

- Altered sleep and eating patterns

- School absence

- Decreased wellbeing

- Dental extraction due to tooth decay (increasing risk of dental problems later in life).

- Decay can be prevented with control of sugar consumption, while fluoride helps to strengthen the enamel and dentine (whether in toothpaste or applied by dental teams in primary dental care). Tooth decay occurs when bacteria in the mouth use ingested sugar to produce acid, which removes mineral from the enamel and dentine.

- Tooth decay has been the commonest reason for hospital admission among children aged five to nine for the past three years.3 For young children, tooth extractions usually require a general anaesthetic and an admission to hospital. This is associated with increased morbidity, and places financial burden on the NHS.4

- Children from lower socioeconomic groups have a greater prevalence and severity of tooth decay.

- Between 1983 and 2013, there has been an overall improvement in the proportion of children with no visually obvious tooth decay across the UK. Up until 2013, the biggest improvement was seen in England.5

- Wales, and latterly Scotland, have introduced national, system-wide strategies to improve oral health among children: Designed to Smile in Wales from 2009,6 and Childsmile in Scotland from 2011.7 Public Health England established the Children’s Oral Health Improvement Programme Board in 2016 to provide policy steer on improving oral health in children.8 Northern Ireland’s most recent oral health strategy was published in 2007 to run to 2013.9

Key findings

- In the past decade, oral health among children has improved at a faster rate in Scotland and Wales than in England – coinciding with the establishment of their national oral health strategies. In terms of the prevalence of visually obvious tooth decay among 5 year old children:

- England: Between 2008 and 2017, prevalence fell from 30.9% to 23.3% (7.6 percentage point reduction).10

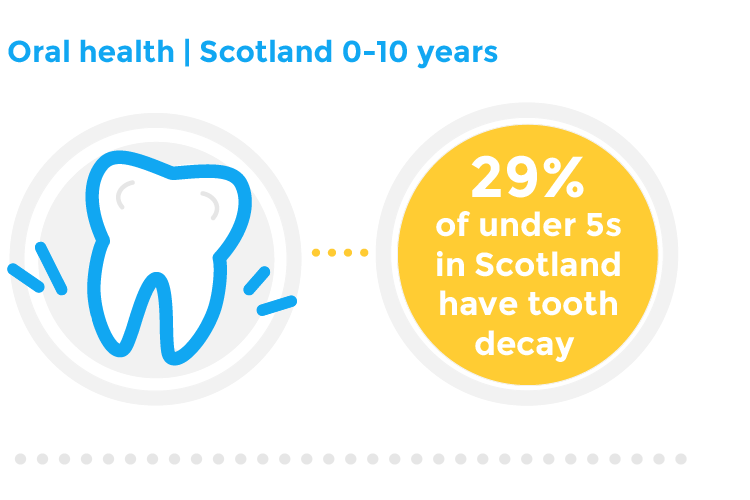

- Scotland: Between 2008 and 2018, prevalence fell from 42.3% to 28.9% (13.4 percentage point reduction).11

- Wales: Between 2008 and 2016, prevalence fell from 47.6% to 35.4% (12.2 percentage point reduction).12

- Northern Ireland: Latest available data from Northern Ireland in 2013 shows 40% of children aged 5 had visually obvious tooth decay.

- This pattern of improvement is mirrored for data relating to children undergoing dental extraction under general anaesthetic:

- England: Between 2011/12 and 2018/19, the rate of children aged 0 to 5 years who have had tooth extractions due to decay has fallen from 3.5 to 2.8 per 1,000 children.13

- Scotland: From 2011/12 to 2017/18, the rate for children aged 0 to 5 years decreased sharply from 3.7 to 2.3 per 1,000 children.14

- Wales: From 2014/15 to 2017/18, among 0 to 2 year olds in Wales, the rate of general anaesthetics performed for dental reasons fell from 2.8 to 1.7 per 1,000.15

- Northern Ireland: no recent routine data were publicly available.

- Children from lower socioeconomic groups are more likely to be at risk of tooth decay prevalence and severity. In England, while 77% of 5 year old children were free of visually obvious tooth decay in 2017, there are significant regional inequalities, with children from the most deprived areas having more than twice the level of decay compared with those from the least deprived.16

Uses data for children in reception/aged 5/P1. For Scotland, 2019 data was not included as the report has data for P7 not P1 as used for previous years.

Rates calculated using the number of children admitted and the population of children. If population numbers were not provided, these were obtained using mid-year estimates from the Office of National Statistics.17

For England, this is data on tooth extractions due to decay for children admitted as inpatients to hospital, aged 10 years and under.

For the 2018/19 England data period a large proportion of records for East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust (code RXC) have missing information for the condition the patient was in hospital for and other conditions the patients suffers from, and this will have affected the calculation of the numerator for this indicator. The effect at England level is likely to be small.

What does good look like?

National oral health strategies for children and young people across the UK. As described above, since major oral health preventive programmes were introduced in Scotland and Wales the rate of improvement in oral health in those countries has markedly outstripped the progress in England. A system-wide approach to improving oral health allows the development of pathways across the public sector including early years, health visiting and dental services. This should confer improvements to oral health and associated benefits for the most vulnerable children and young people.

Encourage good oral hygiene: Prevention schemes in Wales (Designed to Smile) and Childsmile (Scotland) target young children to encourage reduction in sugar consumption and provide supervised toothbrushing support. Distribution of free tooth brushing packs by health visitors to families in groups at high risk of poor oral health is cost-effective and recommended by NICE.18 We welcome the recent progress on rolling out a school toothbrushing scheme in pre-school settings and primary schools in England.19

Reducing sugar consumption: We welcome national efforts to reduce children’s access to sugary food and drinks, including the introduction of the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) in 2018; which should be maintained. The level of free sugar content within infant foods for under 2s should be reviewed.

Water fluoridation: Areas with higher levels of fluoride in drinking water have lower rates of tooth decay and general anaesthetics for dental extraction. Department of Health and Social Care recommends water fluoridation as a safe and effective evidence-based public health measure to reduce the prevalence and severity of tooth decay, and reduce dental health inequalities.20 The Government’s recent Prevention Green Paper outlines a commitment to explore ways of removing funding barriers in order to encourage more local areas to fluoridate water, particularly in areas where there is a high prevalence of tooth decay.20

Review of access to dental care. Children should have timely access to preventative dental health checks but also to services if tooth decay has developed. NICE guidance recommends all children should visit the dentist once every 12 months22 and the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry encourage all children to have a ‘Dental Check by One’ or as soon as their first teeth erupt.23 Despite these recommendations, 77% of under 2s in England did not visit a dentist in 2018.12 In Wales, only 27% of practices are accepting new child NHS patients.25

My foster carer has shown me how to clean my teeth.

Policy recommendations

- UK Government should commission a review into the factors affecting access to primary, secondary and emergency dental care, with a view to addressing inequalities in England.

- Department of Health and Social Care should deliver a public health messaging campaign on children’s oral health. The campaign should raise awareness of factors contributing to poor oral health (i.e. diet / tooth brushing) and how to access services in a timely manner (i.e. Dental Check by One).

- UK Government should provide preventative support programmes for children and families to enable them take up positive oral health habits (i.e. through supervised tooth brushing schemes). The programme should be targeted at children aged 0-7 in England and should draw on comparable schemes in Wales (Designed to Smile), Scotland (Child Smile) and Northern Ireland (Happy Smiles).

- UK Government should provide resource and support for Local Authorities to implement fluoridation of public water supplies, particularly for areas where there is a high prevalence of tooth decay.

- Scottish Government should commission a review into the factors affecting access to primary, secondary and emergency dental care, with a view to addressing inequalities in Scotland.

- We welcome NHS Scotland’s Child Smile Programme, which provides oral health resources for families and professionals and offers targeted support (supervised tooth brushing / dental packs) for children aged 3- 12. Funding and resource should be provided for Child Smile to continue.

- Scottish Government should resource and support fluoridation of public water supplies, particularly for areas where there is a high prevalence of tooth decay.

- Welsh Government should commission a review into the factors affecting access to primary, secondary and emergency dental care, with a view to addressing inequalities in Wales.

- We welcome Designed to Smile, which provides support programmes for children and families to enable them take up positive oral health habits (e.g. through supervised tooth brushing schemes). Welsh Government should ensure sufficient funding and resource for Designed to Smile to continue.

- Designed to Smile should provide a public health campaign to to raise awareness of factors contributing to poor oral health (ie diet / tooth brushing) and how to access services in a timely manner (ie Dental Check by One).

- Welsh Government should resource and support fluoridation of public water supplies, particularly for areas where there is a high prevalence of tooth decay.

- We support the Northern Ireland British Dental Association’s call for an updated Oral Health Strategy for Northern Ireland, which was last published in 2007 and in terms of children’s oral health, was based on data from the 1993 Children’s Dental Health Survey. The updated strategy should include:

- A review into the factors affecting access to primary, secondary and emergency dental care, with a view to addressing inequalities in Northern Ireland.

- A public health messaging campaign on children’s oral health which raises awareness of factors contributing to poor oral health (i.e. diet / tooth brushing) and how to access services in a timely manner (ie Dental Check by One).

- Increased access to support programmes for children and families to enable them take up positive oral health habits.

- We welcome the Happy Smiles programme for pre-school children in Northern Ireland. Funding for the scheme should be provided for the programme to continue and expansion of the programme for older children should be considered.

- Northern Ireland Executive should consider fluoridation of public water supplies, particularly for areas where there is a high prevalence of tooth decay.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Make every contact count. All child health professionals (in particular; paediatricians, health visitors and school nurses) should include oral health in assessment of children’s all-round health. Top tips which may be useful for families include:

- brush with fluoride toothpaste as soon as teeth erupt

- minimise sugary foods and drinks

- attend the dentist regularly for preventive advice and care.

- Remember that poor oral health may be an indication of child neglect.

- Promote the use of personal oral health records. Parents should be encouraged to monitor and record children’s oral health within the Personal Child Health Record (Redbook).

- Further resources:

- Public Health England’s Health Matters – child dental health24

- Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention25

- Child Oral Health – applying all our health26

- The eLearning for healthcare dentistry module delivered by the Royal College of Surgeons of England and Health Education England.27

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

Health and Social Care Information Centre. 2015. Children’s Dental Health Survey 2013. Country specific report: Wales.

Colak, H. et al. 2013. Early childhood caries update: A review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. Journal of Natural Science, Biology and Medicine.

Royal College of Surgeons. 2019. Position Statement: Children’s oral health. London: Royal College of Surgeons.

Knapp, R. et al 2017. Treatment of dental caries under general anaesthetic in children. BDJ Team.

NHS Digital. 2015. Child Dental Health Survey 2013, England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Wales Government and NHS Wales. No date available. Designed to Smile.

NHS Scotland. No date available. About Childsmile.

Public Health England. 2016 Children’s Oral Health Improvement Programme Board Action Plan 2016 – 2020.

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. 2007. Oral Health Strategy for Northern Ireland.

Public Health England. 2018. Oral health survey of five year old children 2017. Available from: PHE

Information Services Division: Scotland. 2019. National Dental Inspection Programme (NDIP) 2019.

Cardiff University. Welsh Oral Health Information Unit. Available from: Cardiff University

NHS Digital. 2020. Tooth extractions due to decay for children admitted as inpatients to hospital, aged 10 years and under. Available from: NHS Digital

Data shared with Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.

Public Health Wales. 2019. Child Dental General Anaesthetics in Wales.

Public Health England. 2018. National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England: oral health survey of five-year-old children 2017: A report on the inequalities found in prevalence and severity of dental decay. London: Public Health England.

Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Mid-2001 to mid-2018 detailed time-series. June 2019.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2014. Oral health: local authorities and partners. Public health guideline [PH55].

Department of Health and Social Care. 2019. Advancing our health: Prevention in the 2020s.

Public Health England. 2018. Water Fluoridation: Health Monitoring Report for England 2018. London: Public Health England.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2004. Clinical Guideline CG19: Dental checks – intervals between oral health reviews.

British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. Date unavailable. Dental Check By One.

NHS Digital. 2019. NHS Dental Statistics for England, 2018-19, Second Quarterly Report.

Public Health England. 2017. Guidance: Health Matters: child dental health.

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, Department of Health and Social Care, NHS England, and NHS Improvement. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2021. London.

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. 2022. Child Oral Health – applying All Our health.

E-learning for Healthcare. Date unavailable. E-Den.