Child poverty

Too many children in the UK grow up in families experiencing poverty and deprivation. Socioeconomic status and geographical variation significantly impact child health outcomes.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- Poverty is associated with adverse developmental, health, educational and long-term social outcomes. Child poverty is linked to a wide range of poorer outcomes, including:

- Low birth weight (200g lower than affluent counterparts);

- Poor physical health (linked to chronic conditions and obesity);

- Mental health problems / low sense of wellbeing;

- Experience of stigma and bullying from peers;

- Academic underachievement;

- Subsequent employment difficulties;

- Social deprivation.1

- Relative poverty compares the income of households with the average household income; in the UK, this is defined as 60% of the current median. After housing costs presents a more accurate measurement of poverty as the cost of housing is essential and unavoidable;2 in 2016/17 the difference between before and after housing costs was 11%.

- Absolute poverty considers the level of income needed to purchase basic goods and services . However, in the UK, this is not so simple, and the UK “absolute poverty” measure is actually defined as less than 60% of median income (anchored at 2010/11 values but adjusted for inflation). In other words, it is not technically an absolute measure at all per se, but a relative measure linked not to current median income but to the historical median income in 2010/11.

- Low income and material deprivation. Material deprivation – the inability to afford basic resources and services – has arguably the greatest impact on children and young people. Low income and material deprivation is defined as household income lower than 70% of median income together with being materially deprived, while severe low income and material deprivation is income lower than 50% combined with high material deprivation. Material deprivation assessed a family’s ability to afford a list of basic children’s items, although each UK nation uses different indices of material deprivation.

- Persistent poverty measures the prevalence of households that have lived in poverty for a prolonged period of time; in the UK, this is defined as households with an income less than 60% of the current median for at least three of the previous four years. One in four lone parents in the UK live in persistent poverty, signaling a concern that children and families struggle to move out of poverty.3

Poverty could mean you would not be able to live a 'normal kid’s life' and might feel empty and useless.

Key findings

- Relative poverty:

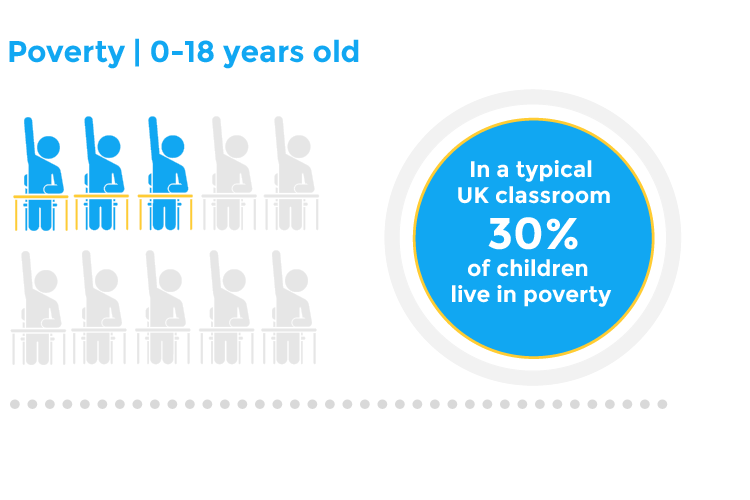

- A total of 4.1 million children live in relative poverty in the UK after considering housing costs, approximately 30% of the population. That means over 500,000 more children are in relative poverty in 2017/18 compared to in 2011/12. This is projected to rise to 5.2 million children by 2022, which would mark a record high in relative poverty rates for UK children.4

- In 2017/18, the proportion of children living in relative poverty after considering housing costs varied between each of the UK nations: 31% in England, 29% in Wales, 24% in Northern Ireland, and 24% in Scotland. Both England and Wales saw a rise of one percentage point from 2016/17 to 2017/18.

- Absolute poverty – 18% of UK children live in absolute poverty, a reduction of eight percentage points from 2002/03 to 2017/18. However, absolute poverty is projected to rise by 2021.5

- Low income and material deprivation:

- 12% of UK children live in low income and material deprivation, a slight reduction of one percentage point from 2010/11 to 2017/18.

- 5% of UK children live in severe low income and material deprivation, worryingly this figure has increased by one percentage point from 2016/17 to 2017/18.

- Persistent poverty – One in four lone parents in the UK live in persistent poverty, signalling a concern that children and families struggle to move out of poverty.

- Poverty is increasing among families who are in work. From 2011/12 to 2017/18, rates of child poverty have increased for all types of working family. Lone parent families working part time and households with only one working parent have seen the sharpest increases in poverty have the last three years. Nearly half of children (47%) in lone parent families live in poverty. 70% of children in poverty are living in a household where at least one parent works.6

- Younger children and children in larger families are at higher risk of poverty

- The risk of poverty for children in larger families (those with 3 or more children) has risen from 32% in 2012 to 43% in 2018, and is projected to reach 52% in 2021.7

- Over a third of children aged 0 to 4 years live in relative poverty after housing costs, and this group makes up more than half of all children in poverty.8

All country/region tables are three-year averages to ensure sufficient sample sizes.

Differing definitions of poverty:

- Absolute low income: less than 60% of median income in 2010/11 values, adjusted for inflation

- Low income and material deprivation: household income lower than 70% of median income together with high material deprivation

- Severe low income and material deprivation: household income lower than 50% together with high material deprivation.8

New questions about four additional material deprivation items for children were introduced into the 2010/11 FRS and from 2011/12 four questions from the original suite were removed. Due to a break in the series in 2010/11 it is not possible to make direct comparisons with results from earlier years for both the combined low income and material deprivation and severe low income and material deprivation.

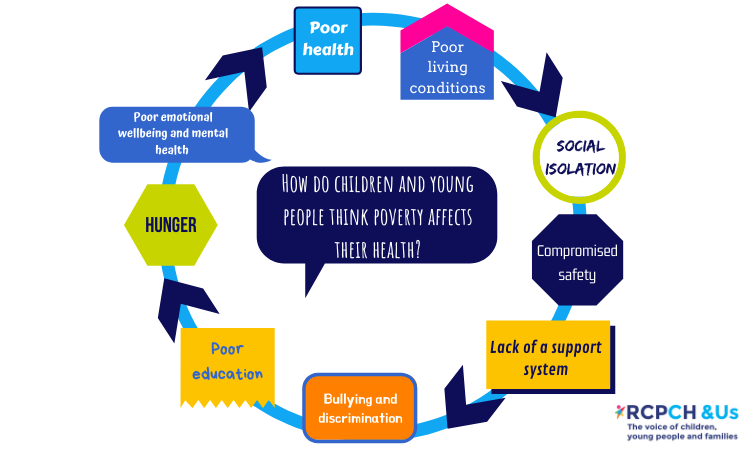

What do children and young people say?

Children and young people told us how poverty can stop you feeling ‘healthy, happy and well’:

- Not enough money for healthy nourishing food, leading to a poor diet and unhealthy eating. It would be easier to get disease and get sick because of poor diet and poor hygiene. It would also be hard to sleep, which would also affect your mental health.

- Not able to afford to go to social events or sports clubs, go on holiday, or go on school trips. You might be left out.

- Can’t afford good housing, could be homeless. You would be lacking basic things like electricity, or hot, clean water – leading to poor hygiene (dirty clothes, hair etc).

- You may end up being bullied, or possibly becoming a bully. People might make fun of you, and you might be bullied because you can’t afford clothes, or have a dirty uniform.

- Poverty would result in poor mental health and could lead to depression or anxiety. You could feel angry and frustrated, and might lash out at people.

- You would become vulnerable and might be exposed to ‘dodgy’ people and drugs. You could be forced to make bad choices and get up to trouble.

What does good look like?

Address the causes of poverty to prevent vulnerable families from falling below the poverty line – in particular, reversing reductions in social security and benefits resulting from welfare reform. Poverty is multi-faceted and identifying the drivers and solutions is complex, but there is little doubt that earnings growth and benefits cuts are leading contributors.14 Low income families receive a greater proportion of their overall household income from welfare payments, meaning earnings growth has reduced overall impact and may explain why rates of in work poverty have increased in recent years. Alongside this, changes to UK benefits systems have negatively impacted low income families, including freezes to working age benefits and tax credits15 and the introduction of Universal Credit.16 Prolonged waiting times for Universal Credit payments, which are routinely paid one month in arrears, has led to a 52% increase in demand for emergency food parcels.17

Set and monitor national targets to reduce and eradicate child poverty. The replacement of the 2010 Child Poverty Act with the Welfare Reform and Work Act marked the withdrawal of UK Government’s national targets to eliminate child poverty. This is despite the evidence that such a policy focus led to a fall in rates of relative child poverty after housing costs from 2009/10 to 2012/13. We welcomed Scottish Government’s commitment within the Scottish Child Poverty Act to reduce child poverty by 2030.18 A lack of legally binding targets coupled with increased pressures on local authority budgets has meant that child poverty has struggled to be seen as a national priority, which requires increased political will to address. National targets and policies should recognise the intersection between poverty and health inequalities.

Provide increased support for children and families living in poverty, or at risk of falling into poverty. The level of support available to children and families living below the poverty line has reduced in recent years,19 slowing the rate at which families are able to move out of poverty. Sure Start schemes – children’s centres offering education, health and family support – have effectively reduced avoidable hospitalisations amongst primary aged children in the most deprived areas.20 Securing ongoing funding for Sure Start provision is crucial or we risk reversing the gains that the programme has achieved to date.

Tackle housing needs for families. Housing costs represent a great proportion of household income, particularly for families on the lowest income quantile as house prices have risen nationally; in 2016/17 37% of children in the bottom quantile lived in privately rented accommodation, compared to 17% in 2005/6.21 The cost of private rent is typically more expensive than social housing and private sector rent has risen by an annual average of 2%22 making housing increasing unaffordable for vulnerable families. Alongside this, there have been reductions in housing benefits, leading to increases in out-of-pocket housing costs. Increasing evidence suggests a rising number of families are living in poor quality accommodation, with detrimental impacts on children’s health. There is also an increasing number of children living in temporary accommodation.

Policy recommendations

- UK Government should provide renewed investment in services for children and families, which support the child’s school readiness.

- UK Government should introduce a cross-departmental National Child Health and Wellbeing Strategy to address and monitor child poverty and health inequalities. The Strategy should:

- Adopt a ‘child health in all policies’ approach to decision-making and policy development, with HM Treasury measuring and disclosing the projected impact of the Chancellor’s annual budget statement on child poverty and inequality. The Government should also collect adequate data to ensure all Departments can consider the impact of policies on child health as accurately as possible.

- Reintroduce national targets to reduce child poverty rates and introduce specific health inequality targets for key areas of child health. Specific Government departments should be responsible and accountable to deliver targets set. The Department for Work and Pensions in particular should undertake a review into the impact of recent welfare changes on child poverty and inequality.

- Provide funding for a child health workforce, that meets demand, and ensure children and young people receive the best possible care. – Include a specific focus for the first 1,000 days of life.

- Scottish Government should action all measures contained in the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act and ensure these actions are appropriately resourced and funded, enabling the interim and 2030 targets to be met on time. The Child Poverty (Scotland) Act progress reports should include the views of children and young people in how these actions impact the (UNCRC).

- Scottish Government should publish the Children and Young People’s Health and Wellbeing Outcomes Framework without delay, to complement the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act.

- Scottish Government should provide renewed investment in services for children and families, which support the child’s school readiness.

- Welsh Government should acknowledge high child poverty rates, review existing programmes and publish a revised Strategy to reduce child poverty. The Strategy should provide national targets to reduce child poverty rates and specific health inequality targets for key areas of child health, with clear accountability across Government.

- Welsh Government should provide renewed investment in services for children and families, which support the child’s school readiness.

- Northern Ireland Executive should achieve the outcomes in the overarching Children and Young People’s Strategy (2019-2029) and expedite the development of the associated delivery plan.

- Northern Ireland Executive should prioritise publication of a successor strategy to the Child Poverty Strategy to continue to monitor the impact of poverty and target intervention where it is needed most. It is encouraging that this strategy is identified in the New Decade, New Approach document as an underpinning strategy for the new Programme for Government.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Health professionals should know how to signpost families to financial support services. It is important to be aware of the circumstances in which children and young people live, and the impact that has on their (and their families’) ability to manage their health and care. An increasingly vital part of a health professional’s role is to signpost families and local sources of expert financial inclusion support for those in financial hardship, and refer them to welfare rights services to ensure they access their statutory benefits and social security entitlements. For example, UK Bill Help provides lists of resources to help families through temporary hardship.

- Food insecurity. It is estimated that in the UK, 3% of the overall population is undernourished23 and 1.9 million children under the age of 15 were living in severe food insecurity between 2014-16,24 with detrimental effects on physical and mental health. Health professionals should be alert to the possibility of food poverty to signpost families to local sources of support (including food banks) and treat nutritional deficiencies where required.

- Advocate for change. Health professionals should work with other sectors to advocate for change and to raise awareness of the impact that poverty has on the health and wellbeing of the children and young people that they care for.

- Resources for more information:

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Jonathan Cushing, RCPCH Education & Training Division

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

The Children’s Society. 2019. What are the effects of child poverty?

Child Poverty Action Group. 2019. Child Poverty Facts and Figures.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2018. UK Poverty 2018: A comprehensive analysis of poverty trends and figures.

Francis-Devine B, Booth L, McGuinness F (2019) Briefing paper – Poverty in the UK: statistics.

Hood A, Waters T (2017). Living standards, poverty and inequality in the UK: 2017–18 to 2021–22

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2018. UK Poverty 2018: A comprehensive analysis of poverty trends and figures.

Sefton T, Tucker J and McCartney C (2019) All kids count: The impact of the two-child limit after two years

Households Below Average Income (HBAI) Statistics 1994/95 to 2017/2018, Department for Work and Pensions.

Households Below Average Income (HBAI) Statistics 2002/2003 to 2017/2018, Department for Work and Pensions.

Households Below Average Income (HBAI) Statistics 2002/2003 to 2017/2018, Department for Work and Pensions.

Households Below Average Income (HBAI) Statistics 1994/95 to 2017/2018, Department for Work and Pensions.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) Persistent poverty in the UK and EU, ONS, Eurostat, Department for Work and Pensions.

Households Below Average Income (HBAI) Statistics 2002/2003 to 2016/2017, Department for Work and Pensions.

Hood, A. & Waters, T. 2017. Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2016-17 to 2021-22. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Barnard, H. 2017. UK Poverty, 2017. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Cheetham, M., Moffatt, S., Addison, M. et al. 2019. ‘Impact of Universal Credit in North East England: a qualitative study of claimants and support staff’, BMJ Open, 2019:9.

Trussell Trust. 2019. 5 Weeks Too Long. London: Trussell Trust.

Scottish Government. 2017. Child Poverty (Scotland) Bill.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2018. UK Poverty 2018: A comprehensive analysis of poverty trends and figures

Catten, S., Conti, G., Farquahrson, C. & Ginja, R. 2019. The health effects of Sure Start. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2018. UK Poverty 2018: A comprehensive analysis of poverty trends and figures

Birch, J. 2015. Housing and Poverty. York: Rowntree Foundation.

World Bank Group. 2016. World Bank Data. World Bank Group

Pereira, A.L., Sudhanshu, H. & Holmqvist, G. 2017. Prevalence and Correlates of Food Insecurity among children across the Globe. Innocenti Working Paper 2019-19. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research.