Child health workforce

The child health workforce comprises paediatricians, children’s nurses, health visitors, mental health professionals, primary care and all other allied health professionals, aiming to provide high quality care for children and young people.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- A child health workforce of sufficient number and skill is crucial to efforts to improve the health of children and young people in the UK: not simply paediatricians, but also children’s nurses, health visitors, mental health professionals, primary care, allied health professionals and many others who contribute to the children and young people’s health care.

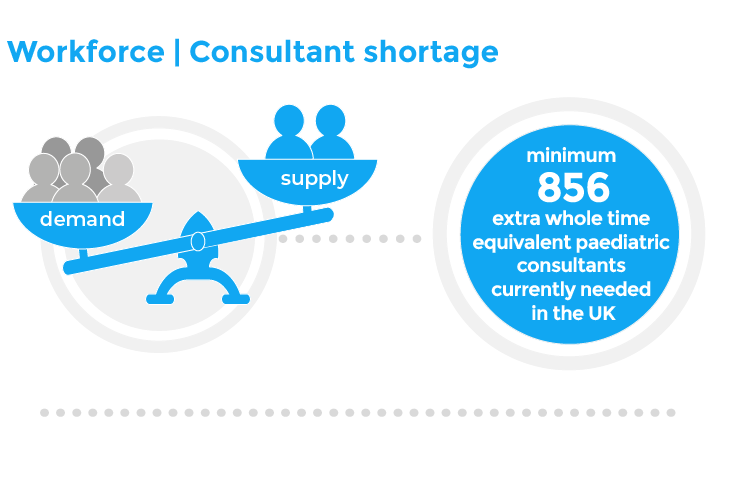

- Demand for child health services outstrips capacity. Demand for paediatric consultants in the UK was estimated to be around 21% higher than workforce levels in 2017.1 Similarly, a survey of paediatric community child health services conducted in 2015/16 estimated that 17.6% of demand was unmet.2

- This means that at least 856 additional consultants in the UK would be needed to meet that level of demand: 642 WTE in England, 82 WTE in Scotland, 73 WTE in Wales and 59 WTE in Northern Ireland.21

- Workforce issues are a significant challenge to child health service delivery and improvement, and a fundamental barrier to children and young people receiving consistently high-quality care. 84% of paediatric doctors stated that vacancies in paediatric training posts and workforce gaps pose significant risk to their service or to children, young people and their families.3

- Working patterns are changing. Paediatric consultants and trainees are increasingly choosing to work less than full time, and senior clinicians are opting for earlier retirement, which pose additional challenges to those presented by increasing demand and workforce attrition.4 As a result, whole time equivalent, or WTE, are used across these indicators. 1.0 WTE denotes full time employment and less than 1.0 WTE refers to less than full time (LTFT) working (0.5 WTE would reflect a post that is half of full-time hours, for example). WTE is therefore often more instructive than a simple headcount, especially when comparing the capacity of the workforce.

- This indicator examines trends in the child health workforce across the UK – paediatricians, mental health services, primary care doctors and child health nursing. There are many more professions with a vital role in child health, including but not limited to: allied health professionals, public health specialists and nurses, social care, early years education and third sector practitioners. However, availability of comprehensive data on these professions, and in particular the difficulties of identifying WTEs with specific child health responsibilities, mean that what follows is inevitably a limited but pragmatic approach.

We need someone to look after the staff too.

Key findings

Paediatricians

- Consultant WTE per 10,000 children and young people have increased in each of the four nations from 2005 to 2017. Throughout this period, Wales had the lowest number of consultants per 10,000 children and young people compared to other UK nations, whereas England has the highest from 2005 to 2013, and Scotland from 2015 onwards.5

- In 2017, consultant WTEs range from 1.9 (Wales) to 2.2 (England).

- The rise in demand has outstripped increases in consultant numbers per population across all four UK nations. While consultant numbers per population have risen over the past decade, the demand for child health services has also risen. From 2013/14 to 2016/17, across the UK, emergency admissions – a marker of acute care needs – rose between 12.7% (England) and 17.8% (Northern Ireland).6

- 3.6% of paediatric doctors in training leave part way through their training programme each year, but the number of new paediatric doctors in training is rising by only 0.9% per year.7, 8

- There is significant variation across the country in the rate and/or number of filled and vacant posts, at both consultant and training grade levels. This reflects the how the mismatch between regional demand and workforce capacity can lead to greater pressures in one region than another.9, 10

Mental health

- The rate of consultant psychiatrists is very similar across the four nations, at between 6 to 7 per 100,000 children and young people.

- Mental health workforce per population is relatively similar across the four UK nations, with the exception of Scotland being comparatively better served for community based psychologists and mental health nurses. Scotland has 36 mental health nurses and 21 clinical psychologists per 100,000 children and young people – which is 56% and 110% greater than next highest UK nations (Northern Ireland and England respectively).

- There are significant vacancies in the mental health workforce. The vacancy WTE in England for child and adolescent psychiatry positions (all grades) between 1 January and 31 March 2018 was 1,019.11

Primary care

- The number of children and young people per fully-qualified GP has remained relatively stable within each country from 2012 to 2018.

- Scotland’s GPs look after the lowest number children and young people per GP in the UK. By contrast, England’s children and young people are least well provided for on average, followed closely by Wales. The one data point available for Northern Ireland places their ratio just behind Scotland.

- GP WTEs have fallen in England. The total fully qualified GP WTE in England in March 2019 was 28,697, representing a decrease of 1.5% from March 2018 and a decrease of 9.5% from September 2015.12, 13

- A stable headcount and shrinking WTE suggests a trend towards LTFT working, exacerbating shortages in the GP workforce across the UK.

Nursing

- Overall, child health nursing numbers have largely declined in England but increased in Wales and Northern Ireland (with no comparable data available for Scotland). England has seen a decline in all nursing numbers, with the exception of children’s nurses in hospital. Wales and Northern Ireland have both, by and large, seen slight increases across child health nursing professionals since 2013 and 2009 respectively. However, the Welsh data is subject to changes in coding style which may partly account for the increase.

- Hospital nurses capacity has increased across the UK. Between 2009 and 2019, England children’s nurses in hospital have increased by 52%, while Northern Ireland’s children’s nursing workforce increased 58.2% in terms of WTE nurses. Similarly in Wales, children’s nurses increased 49% from 2013 to 2018.

- Health Visitors numbers have fallen in England, but rose in Wales and Northern Ireland. England has seen a 25% fall in health visitors since its peak in 2015. In Wales there was a slight increase (from 858 health visitors in 2013 to 876 in 2018). Northern Ireland’s health visitor WTEs rose 34% between 2009 and 2019.

- School nurse WTE have risen in Wales and Northern Ireland, but fell in England. From 2009 to 2019, the WTE school nurses have fallen by 24% in England, but risen by 51.3% in Northern Ireland. Wales has seen a rise of 92% between 2013 and 2018.

- Community nursing WTEs have fallen in England since 2009 by 14%.

- Learning disability nurses fell in England and Northern Ireland, while Wales’ increase may be coding-related. England has seen a 42% fall in learning disability nurses since 2009, and Northern Ireland a fall of 17.3% over the same time period. In Wales, the number rose from 5 in 2013 to 69 in 2018, although there was a known coding issue which may account for a large proportion of this change.

- There is significant geographical variation, not only between the four nations, but within nations too. For instance, the west of Scotland has a relatively high number of health visitor vacancies (88.7) compared to other staff groups in the region, whereas the north appears to lack children’s nurses (46.7) over any other staff group or specialty.14

Additional information

What does good look like?

Improve data quality for child health workforce. The data presented here represent just a small proportion of child health professionals, with many others excluded due to lack of available data. Allied health professionals (AHPs), in particular, are a vital part of the child health workforce and represent a huge contribution to our care – but data on the numbers of AHPs who work with children are limited, and particularly so when many professionals split their time between child and adult services. Better data on the wider workforce is especially important as child health moves away from a medical, hospital-centred approach towards a more integrated model.

Child health workforce strategies should form part of national child health strategies in each of the four nations. The data presented in this chapter reflects a dedicated workforce under huge pressure in difficult circumstances. Each of the four nations must work to support their current staff, build their workforce and fill data gaps.

Investment in child health workforce numbers and training to match demand, and deliver sustainable improvements in outcomes. The child health workforce is experiencing variable levels of growth and decline between different countries and professions. Even in professions where growth in the workforce exists, this is often offset by increasing demand or a decline in WTE. Despite increases over the past decade, Wales and Northern Ireland’s nursing workforce remains under significant strain – even “crisis point”.15 While measures such are upskilling and retention are important, a sustained increase in base numbers is required.

Supporting primary care’s child health capacity and capability. “GPs per population of children and young people” is a crude metric of child health in primary care. Policies that focus on increasing GP numbers is unlikely solve the capacity issue alone, given that LTFT working is becoming increasingly prevalent. Furthermore, in the context of an already under-staffed workforce, the growing demands of an ageing UK population risk crowding out those of the youngest service users.16 Beyond capacity, it is important to continue to develop primary care capability in child health. Increasing formal training in child health in primary care, where the bulk of children and young people’s health contacts occur, remains crucial.

Workforce fit to deliver integrated care for children and young people with complex or changing needs. The nature of ill health among children and young people is changing, and workforce planning needs to recognise the change in their needs, and invest in the right skills to meet those needs. While children’s nursing in hospitals has grown in the last decade, the opposite is true of their counterparts in the community, schools and health visiting. Similarly, in 2015 community paediatrics had a vacancy rate of 8.5%, double that of hospital paediatrics.17 Future investment in workforce should mirror the changing locus of care for children and young people, moving from hospitals to the community, and from care delivered by single institutions to a more integrated approach that crosses organisational boundaries.

Policy recommendations

- We welcomed the publication of the NHS People Plan 2020/21 and its emphasis on flexible working and supporting the workforce is positive. Its recommendations should be implemented in full.

- Scottish Government should provide funding for NHS Scotland to develop a bespoke child health workforce strategy, which espouses a coherent and consistent approach to planning. The strategy should:

- Consider the breadth of the child health workforce including medical, midwifery, nursing, allied health professionals, pharmacists, health visitors and school nurses.

- Address the recruitment and retention of the healthcare workforce.

- Provide adequate time and regular structured support for the healthcare workforce.

- Ensure their healthcare workforce data is robust, reliable and comprehensive.

- Be based around robust and proactive modelling, to better match the changing needs of children and young people with the training and recruitment of our future child health workforce.

- We welcome the publication of Health Education and Improvement Wales ‘Healthier Wales: Our Workforce Strategy for Health and Social Care’ (2019) in draft form. The strategy should be expanded to make explicit recommendations for the child health workforce, which espouses a coherent and consistent approach to planning. The strategy should:

- Consider the breadth of the child health workforce including medical, midwifery, nursing, allied health professionals, pharmacists, health visitors and school nurses.

- Address the recruitment and retention of the healthcare workforce.

- Ensure their healthcare workforce data is robust, reliable and comprehensive.

- Be based around robust and proactive modelling, to better match the changing needs of children and young people with the training and recruitment of our future child health workforce.

- We welcomed the 2018 long-term strategy for Northern Ireland’s health and social care workforce under Delivering Together 2026. The strategy should be expanded to consider the child health workforce, which espouses a coherent and consistent approach to planning. Any specific focus on the child health workforce as part of the strategy should:

- Consider the breadth of the child health workforce including medical, midwifery, nursing, allied health professionals, pharmacists, health visitors and school nurses.

- Address the recruitment and retention of the child healthcare workforce.

- Ensure child healthcare workforce data is robust, reliable and comprehensive.

- Be based around robust and proactive modelling, to better match the changing needs of children and young people with the training and recruitment of our future child health workforce.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Better data. Support data collection of workforce, by participating actively in your professional organisations’ efforts – such as the RCPCH workforce census.18

- Support recruitment and retention in paediatrics. The RCPCH are committed to improving the recruitment and retention of paediatricians, and the #ChoosePaediatrics campaign highlights a number of college-led efforts, as well as resources for members.19

- Maintain the joy in working with children and young people. Amid a climate of increasing burnout among professionals, it is easy to forget that each of us has a critical role to play in recruiting and retaining much needed colleagues to work in child health services – by creating an atmosphere in our workplace, every day, that celebrates the joy of working with children and young people. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Joy in Work project has useful resources and best practice examples to help individuals and teams foster a safe, productive, purpose-driven culture and a positive work environment.20

Contributing authors

- Grace Brown, RCPCH Policy & External Affairs Division

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

RCPCH (2019) 2017 workforce census overview. Available from: RCPCH

RCPCH (2017). Covering all bases: Community child health – a paediatric workforce guide. Available from: RCPCH

RCPCH (2019) 2017 workforce census overview. Available from: RCPCH

General Medical Council (2018). The state of medical education and practice in the UK: 2018. Reference tables – doctors in training. Table 117.

Population data for ages 0-24 from the Office for National Statistics. Paediatric consultant data from 2005 to 2013 available from the RCPCH upon request. 2015 data: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, RCPCH Medical Workforce Census 2015.

RCPCH (2019) 2017 workforce census overview. Available from: RCPCH

RCPCH (2016). MMC Cohort Study (Part 4).

GMC (2019). State of medical education and practice in the UK. Available from GMC.

NHS Digital. (2019) NHS Vacancy Statistics England, February 2015 – March 2019, Provisional Experimental Statistics. Available from NHS.

NHS National Services Scotland (2019). Available from NHS Scotland.

NHS Digital (2018). NHS Vacancy Statistics England – February 2015 – March 2018, Provisional Experimental Statistics. Available from NHS.

NHS Digital (2019) General Practice Workforce, England, March 2019 final.

NHS Digital (2019). General Practice Workforce Final 31 December 2018, Experimental Statistics. Available from NHS.

NHS National Services Scotland (2019). Available from NHS Scotland.

RCN Workforce Data. Available from RCN.

Royal College of General Practitioners (2019). Fit for the Future: A vision for general practice.

RCPCH (2017). Covering all bases: Community child health – a paediatric workforce guide. Available from: RCPCH

RCPCH (2019) 2017 workforce census overview. Available from: RCPCH

RCPCH Careers Campaign. Available from RCPCH.

IHI (2019). Available from IHI.

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2019) Child Health: A manifesto from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health.