Smoking during pregnancy

Rates of smoking during pregnancy have recently stalled in the UK, despite known complications for the mother and child, potentially leading to stillbirth and neonatal death.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- There is no safe level of exposure to tobacco smoke while in the womb. Smoking during pregnancy is a leading factor in poor birth outcomes, including stillbirth and infant (especially neonatal) deaths. Stopping smoking before or during pregnancy will reduce these risks to the child’s health and development.1

- Progress in reducing rates of smoking in pregnancy has stalled in recent years and variation in rates remain depending on geography, socioeconomic status and age.2,3,4,5,6

- Women from deprived backgrounds are more likely to be smokers when they become pregnant. They are also less likely to stop smoking during their pregnancy or after the birth of their child. Younger women (particularly those under the age of 20) are most likely to smoke during their pregnancy.7

- Smoking in pregnancy is routinely recorded during antenatal and postnatal care, but at different stages among the four nations: from antenatal booking, to time of delivery, to first postnatal review with health visitors.

Key findings

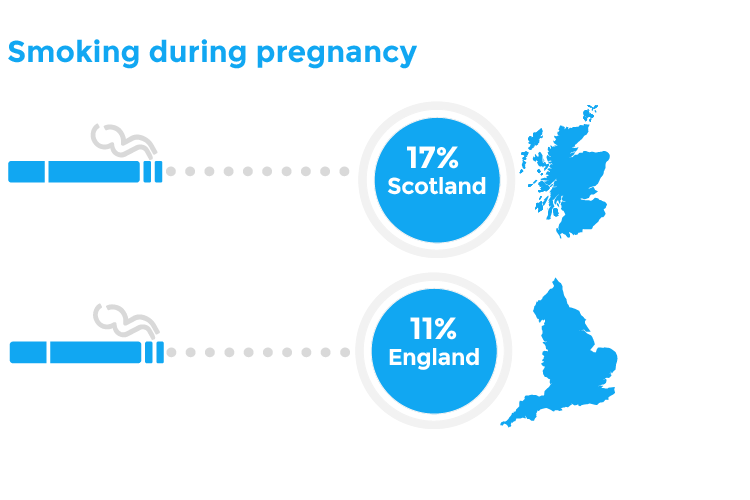

- In Northern Ireland, 13.2% of women reported they were smoking at the time of booking in 2018/19, which has fallen from 15.3% in 2010/11.5 A similar falling trend has been seen in Scotland, with 14.6% of women smoking at the time of booking in 2019, compared to 21.0% in 2010.3

- In England and Wales, smoking status is available at the time of delivery:

- In Scotland, the proportion of women reported as smokers at their first health visitor review after birth has increased from 14.8% to 16.7% from 2014/15 to 2018/19.4

- There is a notable difference in smoking rates between women in the most and least deprived areas in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Over a quarter of women (26.6%) in the most deprived group were recorded as smoking at the first health visitor review in Scotland, compared to 3.3% in the least deprived group.3 This is mirrored in Northern Ireland.5

Figures are likely to be underestimates, as the lack of disclosure of smoking during pregnancy can be up to 25%.8

What does good look like?

Meeting Government targets to create a tobacco free generation, by 2030 in England10,11 and 2034 in Scotland.12 We welcome the publication of tobacco control plans in England13 and Scotland.14 The Department of Health and Social Care’s (DHSC) 2017 plan includes an ambitious target to reduce the prevalence of smoking in pregnancy in England to 6% or less by the end of 2022 – five percentage points from the current level in England, and locally a level which only 28 out of 195 Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)meet in 2018/19. Stagnation in progress to reduce rates of smoking during pregnancy indicates the necessity for further action to meet national targets.

Additional support for smoking cessation during pregnancy. A central element of Government tobacco control strategies is offering support through local NHS stop-smoking services. However, stop-smoking services are most commonly commissioned and funded not by the NHS, but local authorities – and total funding for this has fallen by 36% between 2014/15 and 2018/19, with 31% of local authorities offering no stop-smoking services at all.14 Furthermore, while these services are effective,15 quit rates continue to be consistently lower among certain groups, including pregnant women with a lower socioeconomic status and younger women. Evidence from Scotland has shown that tailored health promotion programmes designed specifically to reduce tobacco use in pregnant women in deprived areas have been successful in leading to higher quit rates, compared to less-tailored stop-smoking services.

Policy recommendations

- As part of the Healthy Child Programme, health visitors (or other community based health professionals) should offer all pregnant women breathalyser tests to monitor smoking prevalence, alongside advice on local smoking cessation services.

- UK Government should resource Local Authorities to introduce incentive schemes to support women to stop smoking during their pregnancy.

- Scottish Government should set smoking reduction targets for pregnant women. These targets should be monitored and reported against regularly.

- As part of the Child Health Programme, health visitors (or other community-based health professionals) should offer all pregnant women the opportunity to have exhaled carbon monoxide breath testing to monitor smoking prevalence, alongside advice on local smoking cessation services.

- Local Authorities should introduce incentive schemes to support women to stop smoking during their pregnancy.

- Welsh Government should set targets to become a tobacco free generation (defined as a smoking prevalence of <5%); including smoking reduction targets for pregnant women. These targets should be monitored and reported against regularly.

- As part of the Healthy Child Wales Programme, health visitors (or other community based health professionals) should offer all pregnant women breathalyser tests to monitor smoking prevalence, alongside advice on local smoking cessation services.

- Local Authorities should introduce incentive schemes to support women to stop smoking during their pregnancy.

- We welcome NHS Wales’ (Maternity and Neonatal Network) Safer Pregnancy Campaign, which includes advice on smoking during pregnancy. Resource for this campaign should be continued.

- Northern Ireland Executive should set targets to become a tobacco free generation (defined as a prevalence of <5%) in the successor Tobacco Control Strategy, when the current one expires in 2022. We welcome the existing target to reduce the number of pregnant women who smoke to 9%.

- Northern Ireland Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts and the Public Health Agency should commit to delivering the extension of carbon monoxide testing to women prior to hospital discharge which will improve postnatal smoke free support as per the Mid-term Review of the Ten-year Tobacco Control Strategy for Northern Ireland (February 2020).

- We welcome the Public Health Agency and Queens University Belfast’s trial on financial incentives smoking cessation scheme for pregnant women, running until November 2020. The Public Health Agency should review and publish the findings of the trial with a view to the making the scheme available to all eligible women in Northern Ireland if successful.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Professionals can make use of free NCSCT online training on delivering Very Brief Advice (VBA) and promotingsmoke free homes and cars.16

- Women who live with a smoker are six times more likely to smoke throughout pregnancy and those who live with a smoker and manage to quit are more likely to start smoking again once the baby is born.17 Professionals should enquire about the whole household and offer stop smoking services as appropriate. Child health professionals should take the same proactive approach to consultations with adolescents, especially young women.

- Professionals should enquire about other harmful behaviours during pregnancy, such as alcohol and substance use.

- Clinical guidance is available in NICE guidance.18 Recent evaluation of the Saving Babies Lives Care Bundle has found inconsistent practice in relation to implementing NICE guidance in England.19

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Alison Firth, RCPCH Policy & External Affairs Division

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

Fingerhut, L.A. 1990. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health.

NHS Digital. 2019. Statistics on Women’s Smoking Status at Time of Delivery: England.

ISD Scotland. 2019. Births in Scottish Hospitals: Maternity and births.

Information Services Division Scotland. Child Health, Publications, Infant Feeding Statistics, Data Tables, Infant Feeding Statistics.

Public Health Agency. 2019. Statistical Profile of Children’s Health in Northern Ireland.

Welsh Government. 2019. Maternity and birth statistics: 2018.

Smedberg, J. et al. 2014. Characteristics of women who continue smoking during pregnancy: A cross-sectional study of pregnant women and new mothers in 15 European countries. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth.

Dietz, P. et al. 2011. Estimates of nondisclosure of cigarette smoking among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology.

Department of Health & Social Care & Cabinet Office. 2019. Advancing our health: Prevention in the 2020s – consultation document.

Public Health England. 2019. PHE Strategy 2020-2025.

Scottish Government. 2018. Raising Scotland’s tobacco-free generation: Our tobacco control action plan 2018.

Department of Health and Social Care. 2017. Smoke-free generation: Tobacco control plan for England.

Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) and Cancer Research UK. 2020. Many Ways Forward: Stop smoking services and tobacco control work in English local authorities.

Bauld, L. et al. 2010. The effectiveness of NHS smoking cessation services: a systematic review. Journal of Public Health.

Ormston, R. et al. 2015. quit4u: the effectiveness of combining behavioural support, pharmacotherapy and financial incentives to support smoking cessation. Health Education Research.

NCSCT. Date unavailable. Online Training.

NHS Digital. 2012. Infant Feeding Survey – UK, 2010.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2010. Smoking: Stopping during pregnancy and after childbirth.

Widdows, K. et al. 2018. Evaluation of the implementation of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle in early adopter NHS Trusts in England. Manchester: The University of Manchester.