Disability and additional learning needs

Children with disabilities and learning difficulties are identified through the education system and supported with learning provision, but there are different thresholds across the UK.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- Each country in the UK has its own statutory provisions and systems to identify and support children and young people with disabilities and learning difficulties, which is reported as Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) in England and Northern Ireland, Additional Support Needs (ASN) in Scotland, and Additional Learning Needs (ALN) in Wales (since 2018). However, there are different thresholds in each country.

- England: a child or young person has SEND if they have a significantly greater difficulty in learning than the majority of others of the same age, or have a disability which prevents or hinders him or her from making use of facilities of a kind generally provided for others of the same age in mainstream schools .

- Northern Ireland: Criteria for children and young people with SEND are similar to those in England. A more rigorous framework for schools to support children with SEND was passed in the SEND (NI) Act was passed in 2016, but is not yet implemented pending consultation on the regulations and the code of practice.

- Scotland: a child or young person has an Additional Support Need (ASN) if ‘for whatever reason, the child or young person is, or is likely to be, unable without the provision of extra support to benefit from school education provided or to be provided for the child or young person’. This is a wider definition than in England and Northern Ireland, as needs can arise from any factor which causes a barrier to learning, including being bullied, being a young parent or carer, or having a parent in prison.

- Wales: Wales used a very similar definition of SEN as England and Northern Ireland up until 2018 (the period encompassed by the data below). In 2018, the Additional Learning Needs and Education Tribunal (Wales) Act broadened this to providing support for children and young people with Additional Learning Needs (ALN) – those with a learning difficulty or disability (whether the learning difficulty or disability arises from a medical condition or otherwise) which calls for additional learning provision.

- Children and young people with SEND/ASN/ALN are more likely to experience poorer outcomes, such as:

- There is a strong link between low income and higher SEND prevalence. In England, pupils with SEND are twice as likely to be in receipt of free school meals (26.6%) than pupils without SEND (13.9%).4 Families raising a disabled child experience higher living costs than those raising a non-disabled child.5

- There are difficulties in interpreting data on the numbers of children with SEND/ALN/ASN. Thresholds for SEND/ALN/ASN may be subjective. The count is only indicative of the number of children with specific needs, and gives no indication of the magnitude each child’s needs. Rising numbers may be a result of increased awareness and recognition of need, ensuring children have greater access to support. Low numbers may either indicate genuinely low prevalence, or reflect an unmet need.

I have rheumatological issues. I was diagnosed at 11, but you are not supposed to be diagnosed with it until you are an adult or at least 12 so I am special. I am now 14 and had time to get used to the illness, treatments and medication. Both the disease and the medication has changed me mentally and physically. Up until this point, I had never stayed in hospital. When I got told I had to stay in, I walked out of outpatients and just screamed and cried. I didn’t want to be ill.

Key findings

- In England, 14.6% of children in in formal education were identified with SEND in 2018. This figure was 19.3% of pupils in 2007. However, the figures are not directly comparable since there was a change in data collection in 2014, during which children transitioned from Statements of SEND onto Education Health and Care Plans. Since 2016, the proportion of children has been stable at around 14%.

- In Northern Ireland, there has been a rise from 16.0% to 23.0% SEND from 2006 to 2019 (with a peak of 23.3% in 2018).

- In Scotland, there has been a sharp rise from 10.3% to 30.9% in children identified with ASN from 2010 to 2019.

- In Wales, there has been a rise from 18.3% to 22.2% in children identified with SEN/ALN from 2004 to 2019.

What does good look like?

Early identification of need. Often SEND, ALN or ASN are not identified until a child reaches the school environment. Health visitors and early years’ staff, along with teachers and educational professionals, have a vital role to play in helping to identify and assess the needs of children at an early stage. Health professionals, too, have a vital role to accurately identify the needs of young children whose development is different to that expected for age.

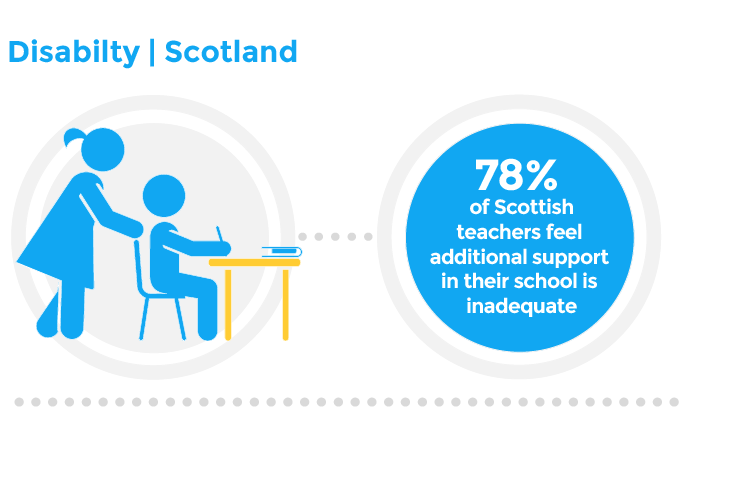

Specialist support for children and young people with a disability or additional learning need, to maximise their developmental, social, educational, and health outcomes as they develop and transition into adulthood. All four nations have statutory provision to support education and health needs for children and young people with SEND/ASN/ALN. Without appropriate resource to support this, there is concern that the educational needs of these children cannot be appropriately met within mainstream education settings, leading to rises in children being educated within specialist provision or home school environments. In England, Ofsted has expressed concern over increasing rates of exclusion for SEND children, alongside insufficient support provided to pupils whose needs aren’t severe enough to require an EHCP.6 A survey of 10,000 teachers in Scotland found that 78% of respondents believed that provision for additional support needs was inadequate within their school.7

Improved data collection to have a fuller picture of needs. These data capture only children and young people who are considered to be above the threshold for having a special or additional need or disability; where this threshold is set will vary by locality. Children who are not enrolled in formal education (many of whom may have very complex needs) are also excluded. These data also provide only a headcount of the number of children with specific needs, and does not paint a picture of the degree and complexity of their medical, social, educational and psychological needs, nor the degree to which there is interaction between each of these areas. Having a consistent and unified method of data collection is vital for better understanding of the needs of these children and young people.

Policy recommendations

- NHS England should deliver commitments from the Long Term Plan for children and young people’s learning disability and autism services, including:

- Improving uptake of annual health check for those over the age of 14; – Supporting the STOMP-STAMP programme

- Funding the Learning Disabilities Mortality Review Programme (LeDeR)

- National learning disability improvement standards to be implemented across all NHS services

- ‘Digital flag’ within systems for learning disability or autism

- Designated keyworker for children with a learning disability, autism or complex needs

- Move toward personalised community care to reduce inpatient care delivery

- NHS Scotland should implement all recommendations from the independent review of Learning Disability and Autism in the Mental Health Act (2019) in full.

- Scottish Government should implement the Proposed Disabled Children and Young People (Transitions) (Scotland) Bill in full, which would ensure development and implementation of a National Transitions Strategy. It would also require Local Authorities to introduce a transitions plan to ensure appropriate care is provided.

- We welcome and support delivery of the ALN transformation programme and commitment for every Health Board to have a Designated Educational Clinical Lead Officer (DECLO).

- We welcome the Children and Young People’s Strategy 2019-2029, which includes children and young people with special educational needs as one of the key areas of focus during the lifetime of the strategy. The Northern Ireland Executive should prioritise the commitment of progressing the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act (NI) 2016 to enable a new and more responsive and effective SEN Framework to be put in place.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Better data on health needs. Health practitioners should understand the needs of their population. To do that, they need to take a proactive approach in identifying each and every need of all children and young people in their care, including diagnoses, family-reported issues, technology dependencies and other factors. To build a wider picture, national collections such as NHS Digital’s Community Services Data Set in England should use shared, consistent coding terminology (using SNOMED-CT as an international standard) to ensure data are both comprehensive and comparable.

- Resources

- RCPCH Disability Matters online learning is a free, flexible learning resource which helps those who work, volunteer or engage with disabled children and young people (from 0 to 25 years) and their families. It covers both physical and intellectual disabilities.8

- Signpost children and young people to appropriate resources. ‘Reach’ in Scotland provides advice for children and young people on understanding rights within schools.9

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

Emerson, E. & Hatton, C. 2007. The mental health of children and adolescents with learning disabilities in Britain. Lancaster University: Institute for Health Research.

Jones, E., Gutman, L. & Platt, L. 2013. Family stressors and children’s outcomes. UK Government: Department for Education.

Gutman, M. L. & Vorhaus, J. 2012. The impact of pupil behaviour and wellbeing on educational outcomes. University of London: Institute of Education.

Special educational needs in England: January 2017, Department for Education, 2017.

Contact a Family. 2014. Counting the costs.

Ofsted. 2017. The Annual Report of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Education, Children’s Services and Skills, 2016/17. Crown Copyright 2017.

EIS. 2019. Additional support for learning in Scottish school education: Exploring the gap between promise and practice. Edinburgh: EIS.