Cancer

Childhood cancers are varied and incidence rates have increased by 15% in the UK since the 1990s; however, more children that are diagnosed are surviving for longer.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- Cancer remains a leading cause of death among children and young people; from 2015 to 2017, there was an average of 240 deaths due to childhood cancer per year in the UK.

- Childhood cancers are varied and do not all share common causal factors. The most common cancer diagnoses in children are:

- Leukaemia

- Brain and other central nervous system (CNS) and intracranial tumours

- Lymphomas.1

- Incidence rates for childhood cancers have risen by 15% in the UK since the 1990s.1

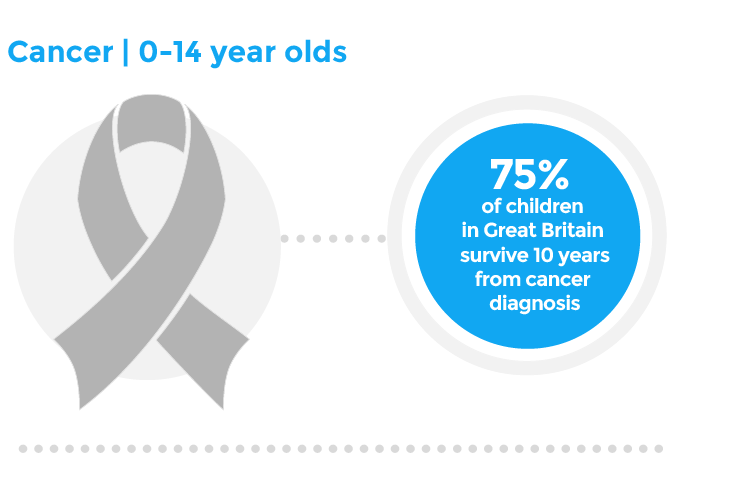

- More children are surviving longer from cancer. From the latest available data in 2010, approximately three quarters of children in Great Britain diagnosed with cancer survived ten years after diagnosis, and 82% survived five years after diagnosis.1 Technological innovations and clinical trials have led to advancements in the delivery of cancer care for children and young people.

I was nine when I was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. My doctors encouraged me to stay in school as much as possible and not let this derail my future.

Key findings

- Between 1990 and 2017, cancer mortality rates among children and young people have steadily decreased across all four nations, across all age groups.

- Cancer mortality rates in the UK are highest among young people aged 15-19, with an overall UK rate of 3.96 per 100,000 in 2017. The lowest mortality rate is seen among children and young people aged 5-14, at a UK average of 2.47 per 100,000.

- In 2017, mortality rates differed among the four nations for each age group:

- Age 0-4 years: Scotland had the highest rates of cancer mortality at 2.9 per 100,000; Wales the lowest at 2.5 per 100,000.

- Age 5-14 years: Scotland had the highest rates of cancer mortality at 2.8 per 100,000; England the lowest at 2.3 per 100,000.

- Age 15-19 years: Scotland had the highest rates of cancer mortality at 4.3 per 100,000; England the lowest at 3.3 per 100,000.

Data taken from the Global Burden of Disease database using the following selections: Measure: Deaths, age bands under 5, 5-14, 15-19 years 1990-2017, Context: Cause, Cause: B.1 Neoplasms, Location: England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Sex: Both, Male, Female, Metric: Rate.2

What does good look like?

Research into better diagnosis, treatment and care for childhood cancer. Progress in childhood cancer survival in the past four decades has been driven by very high involvement of children and young people with cancer in clinical trials, and the changes in practice that followed discovery. Further research should continue to have a broad and balanced approach: on both the basic biology of cancer as well as developing and testing kinder, more effective treatments. Children and young people should be supported to engage in clinical trials, when appropriate.

Earlier detection and diagnoses of childhood cancer. Identifying children with cancer at an early stage can be challenging. They are relatively rare and the symptoms and signs can often be mimicked by more common conditions. Public health messages around early recognition of symptoms remain vital. Health professionals, particularly in primary care settings, need better support, training and access to specialist review, to enable early identification of potential cancer diagnoses.

Support and care for children and young people living with cancer. It is essential that cancer service put children and young people at the centre of care provided to them and that they receive support, information and advice as part of a holistic approach to help them cope with adversity. Inevitably, there will be a need for ongoing investment in end of life care, from palliative care expertise to hospice care services and infrastructure.

Policy recommendations

- NHS England should deliver commitments from the Long Term Plan for children and young people’s cancer services, including:

- Offering all children with cancer genome sequencing;

- Access to CAR-T and proton beam cancer therapies;

- Evidence that children and young person are involved in 50% more clinical trials by 2025;

- All boys aged 12 and 13 are offered vaccination against HPV-related diseases;

- Investment in children’s palliative care services in line with clinical commissioning groups.

- Scottish Government should commit to publishing an impact assessment of the Strategic Framework for Action on Palliative and End of Life Care 2016 – 2021.

- Scottish Government should undertake an impact assessment of the Cancer Plan for Children and Young People in Scotland 2016 – 2019.

- Scottish Government should publish a new cancer plan for children and young people based on the findings of the impact assessment. The plan should consider prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

- Welsh Government should implement recommendations from the Cross Party Group on Hospices and Palliative Care 2018 Inquiry ‘Inequalities in access to hospice and palliative care’, which relate to paediatric palliative care services. Recommendations include: access to out-of-hours services and increased resourcing of community nursing.

- Welsh Government should undertake an impact assessment of the Cancer Delivery Plan for Wales (2016-2020), specifically looking at children and young people’s cancer services, to inform planning for children’s cancer services beyond 2020.

- The Northern Ireland Executive should deliver the commitment to publish the Northern Ireland Cancer Strategy and delivery plan by December 2020, to ensure that innovative treatments and inclusion of children and young people in clinical trials are prioritised.

- There should be investment in children’s palliative services to deliver the objectives in ‘A Strategy for Children’s Palliative and End of Life Care’ (2016-26).

What can health professionals do about this?

- Vigilance for signs and symptoms of childhood cancer. This is important for individual clinicians, but also applies to the whole system. Expert and specialist clinicians have a system-wide responsibility to ensure that all professionals with concerns about early symptoms are supported with access to urgent advice and, when required, access to appropriate and timely specialist review.

- Holistic care for children and young people with cancer, and their families. Children and young people affected by cancer face a huge range of physical, emotional and social challenges, and the impact reverberates around not only close family, friends and carers but to wider family and social circles. Health professionals should be vigilant to this impact, and signpost or refer those affected to appropriate support services, including mental health services and financial and social support where relevant.

- Resources:

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary for “Childhood cancers: recognition and referral” outlines early signs and management for suspected childhood cancers, aimed at all health professionals3

- Headsmart is a set of learning resources relating to early recognition of intracranial tumours, targeted at all professionals who work with children4

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. IHME Data, GBD Results Tool. Available at: GHDX (accessed January 2020)