Young carers

Children and young people with caring responsibilities are more likely to report worse health outcomes for themselves than those who don’t provide care, as they have less individual time.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- Young carers are children and young people under 18 years old who provide unpaid care to a family member who is disabled, physically or mentally ill, or misuses substances. They may care for siblings or other dependents, in the place of other members of their family who are unable to.

- Young adult carers are carers aged 16-24, who are transitioning into adulthood.

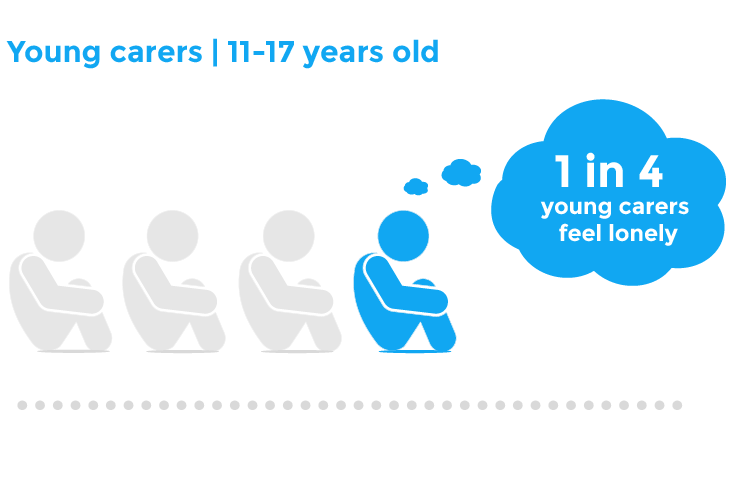

- Young carers experience poorer mental wellbeing than the general population, with 4 in 10 young carers reported feeling sad, 1 in 4 reported feeling lonely, and 1 in 2 reported feeling angry in the preceding week. They are more likely to be bullied in school, to have missed days of school and have fallen asleep in school in the preceding week.1

- The latest comprehensive data on carers were collected in 2011, as part of the most recent UK Census.

A superhero (young carer) helps mum when she has a seizure. Her superpower is that she can talk in a magic language via blinking, since when mum has seizures she can’t speak so they’ve worked out how to say yes/no in blinks, and helps by putting a pom pom by the bed after a seizure to protect the head and to make sure that nanny knows.

Key findings

- In 2011, there were approximately 507,000 children and young people aged 0-24 years who were providing unpaid care across the UK. More recent survey data among school-aged children in England suggest this is likely to be a significant underestimate.2

- There were 87,000 more young carers aged 0-24 years in the UK in 2011 compared to 2001. Scotland was the only home country which did not experience a rise during this time.

- In 2011, in England this constituted 2.5% of the 0-24 year old population; 3.2% in Wales; 2.4% in Scotland; and 3.5% in Northern Ireland.

- Older age groups tended to have higher rates of young carers, except in Scotland.

- Scotland had the highest rate of young carers aged 10- 19 years in 2011, but also the lowest rate among those aged 20-24 years (60.1 per 1,000 young people aged 10-19 years; 44.1 per 1,000 aged 20-24 years). Northern Ireland had the highest rate of those aged 20-24 years (78.7 per 1,000).

- A socioeconomic gradient affects some areas of young caring. In Scotland in 2011, 3.1% of young people aged 0-25 years living in the most deprived quintile were carers, compared with 1.7% in the least deprived; and were nearly twice as likely to be caring for 35 hours a week or more (28% in the most deprived quintile compare with 17% of carers in the least deprived).3

- Across all age groups, being an unpaid young carer was associated with worse self-reported health – and the more hours of unpaid work per week, the more likely young carers were to report poor health.

- Young carers are up to 7 times as likely to report not being in good health compared to those who do no unpaid caring.

- Between 9.6% – 20.8% children and young people doing more than 50 hours of unpaid caring a week report being ot in good health.

- One in five young carers aged 16-17 reported a long-term mental health condition compared to one in 15 non-carers of the same age (20% and 7% respectively), based on data from the GP Patient Survey 2018.4

Rate calculated using census data from 2001 and 2011. The calculation included the total number of children within the 0-9, 10-19 and 20-24 age bands and the total population of the age group.

Additional information

What does good look like?

Making young carers more visible. Local authorities have a statutory responsibility to identify young carers and assess their needs and those of the family.5,6,7 However, only 19% of young carers report that they have ever had any such assessment,8 and it is vital that Local Authorities assess and address the needs of this hidden group.

Recognising and managing poor mental and physical health. Young carers become vulnerable when their caring role puts at risk their emotional or physical wellbeing, and their prospects in education and life. Health professionals, schools and others who come into contact with young carers must recognise that they are a potentially vulnerable group of children and young people who require a proactive approach to the assessment and management of their health and wellbeing.

Ensuring young carers have access to support. Nearly two-thirds of young carers report having received no multiagency support.8 There should also be investment in services which build young carers’ confidence and improve their wellbeing, such as those which provide opportunities for respite and socialisation.

Participation in education and training. Young carers are more likely to have worse educational attainment, more likely to be NEET, and more less likely to be in higher education than those who have no regular unpaid caring responsibilities.9 Educational outcomes are strongly linked to health outcomes in later life, and support for educational participation is vital to improve the life chances of these children and young people. Schools should be encouraged participate in programmes which equip schools with the skills to identify, support and nurture pupils who are also young carers – such as Young Carers in Schools in England, or Supporting Young Carers in Schools- Wales.10, 11

Transition assessments are vital, to provide a route for ongoing support as young carers reach adulthood. In England, young carers must undergo local authority transition assessments when it would be of ‘significant benefit’ to the individual, and must have one before they turn 18 years old.12

Policy recommendations

- We welcomed the Carers Action Plan 2018–2020, as a cross-Governmental programme to support carers in England, including young carers. Resource should be provided to ensure implementation of actions within the Plan.

- UK Government should provide adequate funding to Local Authorities to resource and commission annual health assessments for all young carers.

- We welcome the Carers (Scotland) Act 2016, which places a duty to provide the Young Carer Statement and to involve young carers in hospital discharge planning. Adequate resource must be provided to ensure these are implemented effectively. Scottish Government should monitor the Act and routinely publish progress.

- Scottish Government should provide adequate funding to Local Authorities to resource and commission annual health assessments for young carers.

- Welsh Government should deliver the recommendations made by the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee in its 2019 report ‘Caring for our future’, including providing guidance and resource to ensure that young carers receive annual health assessments.

- We welcome the introduction of national Young Carers ID cards, to enable young carers to access multi-agency support. ID cards must be made available for all young carers aged 0-18.

- The Northern Ireland Executive should deliver on the commitment in the Children and Young People’s Strategy 2019-29 to ensure that children and young people acting as carers receive the support they need to fully undertake their education and have opportunities to relax, socialise and have breaks from their caring responsibilities. Young carers should also be able to access annual health checks.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Active enquiry. Many young carers may not recognise that they are providing caring duties at all, let alone recognise that they have specific needs. Health professionals, schools and others who potentially come into contact with young carers in their professional capacities must not only actively enquire whether their patients are carers, but also about their family circumstances in order to ascertain whether they undertake any caring duties.

- Ensure that young carers (and their family) are told about their statutory rights (such as the right to a needs assessment in England, and that social care must repeat this assessment every time the young carer’s circumstances change including transition assessments before their 18th birthday).

- Direct young carers to sources of support. Professionals should be able to sensitively direct carers and their families to possible routes of financial, educational and health support, which varies across the UK.13, 14, 15

- Remind young carers who are aged 16 years and over that they are entitled to apply for Carer’s Allowance15 (and in Scotland, those who are not eligible for the Allowance may also apply to the Young Carer’s Grant).16

- Helping their family members to access support will have an indirect but important impact on the lives of the young carers themselves.

- Celebrate young carers. Young carers are often ‘experts’ in care, and their contribution should be valued and recognised. Most young carers find it rewarding, and feel rightly proud of their role and the skills they are developing.17

- Resources:

- Training resources to help with improving the identification and support of young carers from the Carers Trust.18

- The Children’s Society’s Include service for young carers has a website with a database of local carers services,19 and resources and practice toolkits for professionals (including some specifically designed for health professionals).20

- Carer passport schemes to provide a record of identification of a carer to improve access to support and services.21

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

Department for Education. The lives of young carers in England: Qualitative report to DfE. 2016.

Joseph, S, et al. (2019) Young carers in England: Findings from the 2018 BBC survey on the prevalence and nature of caring among young people. Child Care Health Dev. 45: 606– 612. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12674

Scottish Government (2015) Scotland’s Carers: An Official Statistics Publication for Scotland. Available from: Scottish Government

Bennett, L (2019) ‘Think data is dull? Get excited by what it’s revealing about carers’. Available from: NHS England

Department for Health and Social Care. Carers Action Plan 2018-20. 2018.

Carers (Scotland) Act 2016. Available from: Legislation.gov.uk

Social Services and Wellbeing (Wales) Act. Available from: Legislation.gov.uk

Department for Education, The lives of young carers in England omnibus, January 2017.

The Children’s Society, Hidden from view. The experience of young carers in England, May 2013.

Care Information Scotland. Young Carer Grant. Available from: Young Scot

NI Direct website article, ‘Carers and learning’. Available from: NI Direct

Department for Education, The lives of young carers in England: Qualitative report to DfE (pdf). February 2016

Carers Trust (2018). Training resources to help with improving the identification and support of young carers. Available from: Carers Trust Professionals

Carers UK. 2017. Carer Passport. Available from: Carer Passport