Children in the child protection system

Some children require targeted support to ensure they have a healthy and happy childhood. Emotional abuse and neglect remain top reasons children are within the child protection system.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- A child subject to a Child Protection Plan (CPP) or on the Child Protection Register (CPR) has been identified as being at risk of harm or experiencing harm. Children in the child protection system are more likely to experience a poorer physical and mental health.1

- Children may experience, or be at risk of, different types of harm. Neglect and abuse, (including physical, emotional or sexual abuse, and fabricated or induced illness), can have serious long-term effects on a child’s social, emotional and physical health and development, and educational outcomes.2,3 Children and young people who experience one form of abuse often experience other forms, and neglect is a key and recurring theme in serious case reviews.4,5

A serious case review is conducted when a child dies, or is seriously harmed, as a result of abuse or neglect. The reviews are shared in an effort to improve how health professionals and agencies can prevent future similar incidences from occurring.

- Official figures underestimate the true prevalence of child maltreatment, as it is often underreported to child protection agencies.6 The data below should therefore be interpreted with caution as there are likely to be cases of child abuse which remain unknown to authorities.

- There is increasing evidence showing that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have a negative impact on long term health and wellbeing outcomes. It is important to approach an understanding of adversity in childhood within the wider social context of factors which impact children and families. Safeguarding services have typically been designed around younger children and their families, and not with due consideration on ‘contextual safeguarding’, addressing the needs of those who are vulnerable to abuse or exploitation outside their families. Some examples of these types of situations include: online abuse, exploitation by gangs, involvement in serious youth violence and county lines.

- There is no “right rate”. There are difficulties in interpreting data on the numbers of children in the child protection system. Low numbers may either indicate low levels of abuse, low levels of reporting or a poorly functioning child protection system. Equally, higher numbers could reflect an increase in abuse, increased reporting to social services or greater community awareness.

Key findings

- From 2004 to 2018, the rate of children subject to a CPP or CPR has increased in all four UK nations.

- England experienced the greatest increase, rising from 24 to 45 per 10,000 children under the age of 18.

- Northern Ireland experienced a sharp rise between 2004 (32) and 2009 (57.5), though the rates have now declined to 47.7 per 10,000 in 2018.

- Scotland experienced a more gradual increase from 2004 to 2018 – from 21 to 26 per 10,000.

- Wales has seen a rise from 33 to 47 per 10,000 from 2004 to 2018.

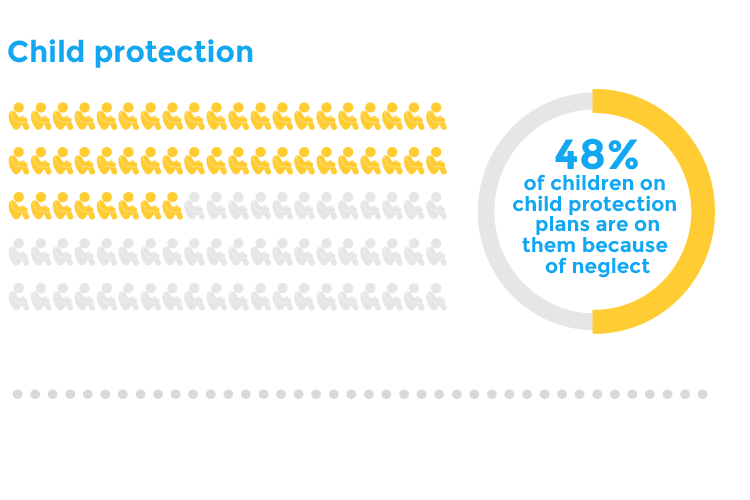

- The most common reasons for being the subject of a CPP or CPR vary across the UK. Direct comparisons cannot be made between the four nations, as the classification criteria for different categories of abuse vary widely.

- England and Wales neglect and emotional abuse remain the most common reasons. Between 2002 and 2018 the number of children subject to a CPP or CPR due to emotional abuse has almost doubled in both England and Wales.

- Northern Ireland neglect and physical abuse are the most common reasons for being on a CPR. The number of children subject to a CPR due to physical abuse and multiple causes has increased, while there has been a decrease in referrals for neglect, emotional abuse and sexual abuse.

- Scotland emotional abuse and parental substance misuse are the most common reasons for being on a CPR. Scotland has seen a rise in the proportion of concerns relating to domestic abuse.7

Rates calculated using ONS population estimates.8

There are differences between the nations in the criteria for recording and the classification of categories of abuse or concerns. Scotland records a wider range of concerns that are not categorised within the other UK nations.9 These include: child placing themselves at risk, child sexual exploitation, parental mental health problems, non-engaging family, domestic abuse, and parental substance misuse (these have been grouped as ‘other’ in the above graph).

Doctors need to know that children are not always happy.

What does good look like?

All children have a right to be protected from harm. Child rights are enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), particularly Article 6 (life, survival and development), Article 19 (protection from violence, abuse and neglect), Article 20 (children unable to live with their family) and Article 39 (recovery from trauma and reintegration).10 Health services must embed these rights throughout their practice and policies.

Support for a public health approach to national preventative strategies. A public health approach to childhood adversity requires collaboration across all parts of the system to coordinate cross- sectoral interventions at the level of society, community and the individual.11 This requires significant investment in upstream prevention and early intervention, to counteract factors which perpetuate the intergenerational exposures to ACEs and other risks.

Multidisciplinary and multiagency safeguarding working. Working Together to safeguard children provides the legislative framework from within which agencies should cooperative to provide a child-centred approach to safeguarding.12 Multi-agency working is also key to safeguard children and young people from the emerging threats such as exploitation by gangs or online abuse.

Better, more comprehensive data on child protection. Accurate knowledge of the number of children in the care system and the reasons for being in the system provides some indication of the number of children at risk of harm in each of the four UK nations and the additional support required to meet their health needs. A broader range child protection indicators such as that published by the NSPCC13 would be a useful addition to official statistics.

Older children and young people in the child protection system are particularly vulnerable. Current systems for child protection and youth justice do not work effectively enough for older children and young people, and there is a pressing need for new strategy, policy and guidance for safeguarding this under-represented group – in particular, better transitional support as they move into adulthood.14

Policy recommendations

- UK Government should consult on incorporating the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child into domestic law.

- We welcome the Department for Education’s ‘Together, we can tackle child abuse’ campaign, which recognises the fundamental right of all children and young people to live free from abuse and neglect and encourages reporting any concerns to the local council. Resource should be provided for this campaign to continue.

- Scottish Government should ensure that investment in services for children and young people in the child protection system reflects the long term costs of not supporting the child, to ensure a holistic approach to their follow-up healthcare.

- Welsh Government should publish an impact assessment report from the National Action Plan Preventing and Responding to Child Sexual Abuse by the end of 2022.

- We welcome Public Health Wales’ adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) hub, which should be regularly updated with information and resources.

- The Safeguarding Board Northern Ireland should ensure the delivery of the priorities of the Child Protection Sub-Group to continue work on measuring outcomes for children in the child protection system as per the Safeguarding Board Northern Ireland Report 2018/19.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Embed the rights of children and young people into health services. Advice and resources on how to utilise the UNCRC rights within practice are available from the RCPCH.15

- Consider the child protection needs of high risk groups. All children and young people have a right to protection, but certain groups of children and young people are a particularly high risk, such as those with mental health conditions or disabilities, or refugee and asylum seeker children. Health professionals should take a proactive approach to ensure early intervention, signpost vulnerable children and families to sources of support, and lead multi-agency working across health, education and social care as appropriate.

- Advocate for local children, young people and their families. Use available data to articulate the needs of the local population, and advocate to local decision makers and commissioners not only for well-resourced child protection mechanisms, but for system-wide interventions to reduce upstream causes of intergenerational adversity.

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Charlotte Jackson, RCPCH Research & Quality Improvement Division

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

- Nish Talawila, RCPCH Research & Quality Improvement Division

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

NSPCC (2016) It’s time: campaign report. London: NSPCC.

Cheatham, C.L. et al. (2010) ‘Declarative memory in abused and neglected infants’, Adv Child Dev Behav, 38, pp.161-182.

Raws, P. (2018) Thinking about adolescent neglect: A review of research on identification, assessment and intervention. The Children’s Society: 2018.

Claussen, A.H., Crittenden, P.M. (1991) ‘Physical and psychological maltreatment: Relations among types of maltreatment.’, Child Abuse & Neglect, 15(1), pp.5-18.

Gilbert, R., Kemp, A., Thoburn, J., et al. (2008) ‘Recognising and responding to child maltreatment’, The Lancet: Child Maltreatment Series, 373, 9658, pp.167-180.

Bentley, H. et al. (2017) How safe are our children? 2017: the most comprehensive overview of child protection in the UK. London: NSPCC.

Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Mid-2001 to mid-2018 detailed time-series. June 2019.

Scottish Government (2019) Children’s social work statistics 2017-2018.

Office of the High Commissioner (1990). Convention on the Rights of the Child.

BMA (2018) Growing up in the UK 2016: progress report.

HM Government. 2018. Working Together to Safeguard Children: A guide to interagency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children.

Bentley, H. et al. (2017) How safe are our children? 2017: the most comprehensive overview of child protection in the UK. London: NSPCC.

Firmin, C., Horan, J., Holmes, D. & Hopper, G. (2019) Safeguarding during adolescence: The relationship between Contextual Safeguarding, Complex Safeguarding and Transitional Safeguarding. Research in Practice. University of Bedfordshire. Rochdale Borough Council. Contextual Safeguarding Network.