Immunisations

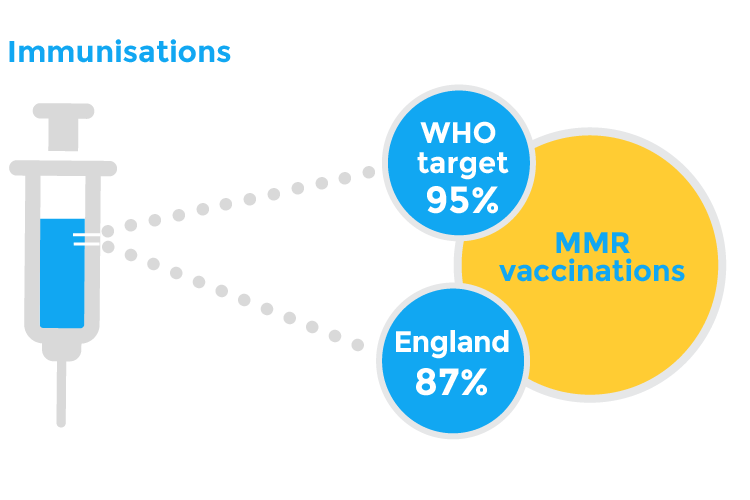

Vaccination rates above 95% provide immunity and protection for wider society and can lead to the elimination of some disease; the UK is not meeting this target for MMR vaccination.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- Immunisation is a safe and highly effective way to protect children and young people against serious and potentially fatal diseases.1The UK national childhood immunisation schedule includes a number of different vaccinations. While it is critical to scrutinise the uptake of all routine childhood (and indeed adolescent and maternal) immunisations, this indicator focuses on only two of the vaccines offered in early childhood.

- The 5-in-1 vaccination protects against five diseases: diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough (pertussis), polio and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib); a single injection administered on three separate occasions at 8, 12 and 16 weeks of age. In Autumn 2017, this was replaced with a 6-in-1 vaccination which additionally includes a vaccine that protects against hepatitis B (HepB).2

- The MMR vaccine protects against measles, mumps and rubella. This vaccine is single injection administered at 1 year of age and at 3 years 4 months of age or soon after.3

- High vaccination rates provide increased probability of immunity throughout the population (herd immunity), which is particularly important for protecting individuals who cannot be vaccinated, and can also lead to the elimination of some diseases. Even when a disease is no longer common in the UK, without sustained high rates of vaccination it is possible for these diseases to return4 as demonstrated by recent measles outbreaks.5,6

As an Autistic person, I feel upset with the link between vaccinations and ASD - it’s horrible for us! I do agree with vaccinations.

Key findings

- From 2005 to 2014, uptake of vaccinations has generally improved. Signs of decline are evident from 2014 to 2018, however, for both the 6 in 1 and the MMR vaccinations:

- In 2017, all four UK nations fall short of the 95% WHO target for the 2nd dose of MMR.7 In 2018, uptake rates in the UK for the second dose of MMR varied from 86.4% in England,8 92.2% in Wales,10 91.2% in Scotland11 and 91.8% in Northern Ireland.9

- Vaccine uptake rates for both the 6-in-1 vaccine and MMR vaccine are considerably lower in England in comparison to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Data for England and Wales are presented in financial years, data for Scotland and Northern Ireland are presented by calendar year.

England: The DTaP/IPV/Hib (5-in-1) vaccine was replaced by the DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB (6-in-1) vaccine in August 2017. Therefore the 12 month age cohort in 2018/19 (born in 2017/18), will have received either the 5-in-1 or the 6-in-1 vaccination, depending on when in the year they were vaccinated.

Scotland: The 6-in-1 vaccine (3 doses) protects against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and Hepatitis B. The 6-in-1 vaccine, which includes protection against Hepatitis B, replaced the 5-in-1 vaccine from October 2017.

Scotland: The values for 2005 – 2010 for the 5 in 1 vaccine were calculated by using the average of the five individual vaccines.

Northern Ireland: The values for 2017 and 18 were calculated using the average of the quarterly data presented. Percentages presented are for each calendar year.

Data for England and Wales are presented in financial years, data for Scotland and Northern Ireland are presented by calendar year.

England: The DTaP/IPV/Hib (5-in-1) vaccine was replaced by the DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB (6-in-1) vaccine in August 2017. Therefore the 12 month age cohort in 2018-19 (born in 2017-18), will have received either the 5-in-1 or the 6-in-1 vaccination, depending on when in the year they were vaccinated.

What does good look like?

An effective vaccination programme be taken up by 95% of the population, to ensure the greatest number of children and young people are protected.12 Vaccine coverage should be increased from early childhood to adolescence, with a particular focus on groups where uptake rates are known to be lower. Targeted public health messaging should take causes of inequalities in vaccine uptake into account; for example, ethnicity, deprivation, geography and religious belief.13,14,15 Additionally, there are other groups including unregistered children, younger children from large families, children with learning difficulties, looked after children and those from non-English speaking families that are more likely to not be fully immunised.16,17,18

Improved understanding of why immunisation rates aren’t improving. There is currently no compelling evidence to suggest anti-vaccine groups and social media messaging have had a major impact on parental confidence. Although health professionals should by no means be complacent about this in the face of rising cases of misinformation, research suggests that only about 1-2% of parents refuse all vaccinations, and parents and carers seem in general to have confidence in national immunisation programmes.19 In fact, the reasons for under immunisation are more complex20 and include practical issues such as lack of easy access to services, cost of travel to services and competing demands on parents’ time as well as parents having questions or concerns about the vaccines.21 Call-recall systems have been shown to increase uptake of vaccines and form an essential part of immunisation programmes.22

A whole system approach to improve vaccine uptake. An effective immunisation programme needs to consider the important role of services, such as health visiting and school nursing, who are ideally placed to contribute to a “whole system” approach to improving immunisation uptake. Youth services, schools and primary care should also be included.

Policy recommendations

- UK Government should urgently publish a vaccination strategy to improve rates of childhood immunisations and ensure that England regains its World Health Organisation measles free status. The strategy should include:

- Resource to expand Department of Health and Social Care’s Value of Vaccines campaign. Currently, it targets individuals and organisations with an interest in public health to share resources and engage in activities, including dissemination guidance for frontline healthcare professionals. The wider campaign should be broadcast through print and digital media and should target the general population, whilst also targeting groups known to be less likely to vaccinate (for example, migrant populations, rural communities).

- Funding for the Healthy Child Programme to develop local community practitioner and health visitor services (or other community-based services), to ensure equitable access to immunisation information and provision.

- The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) should commission UK-wide research into methods to improve vaccination uptake amongst families who make a conscious decision not to vaccinate their child.

- NHS Scotland should ensure full implementation of the Vaccination Transformation Programme by April 2021. We welcome the Programme’s focus on improving IT systems, communication with the public and targeted interventions for vulnerable groups. Funding should be provided to develop local community practitioner and health visitor services (or other community-based services), to improve access to immunisation information and provision.

- Public Health Wales should deliver a public health messaging campaign on the importance of childhood vaccinations and provide signposting for families on how to access vaccination services. The Welsh Government should provide additional funding for this campaign.

- Campaigns should be broadcast through print and digital media and should target the general population.

- Campaign messaging should target groups known to be less likely to vaccinate (for example, migrant populations, rural communities).

- Additional funding should be provided for the Healthy Child Wales Programme to develop local community practitioner and health visitor services (or other community-based services), to improve access to immunisation information and provision.

- Welsh Government and Public Health Wales should urgently publish a vaccination strategy to improve rates of childhood immunisations and ensure that Wales regains WHO measles free status.

- The Public Health Agency should deliver a public health messaging campaign on the importance of childhood vaccinations and provide signposting for families on how to access vaccination services. Northern Ireland Executive should provide funding for campaigns.

- Campaigns should be broadcast through print and digital media and should target the general population.

- Increased campaign coverage should target groups known to be less likely to vaccinate (for example, migrant populations, rural communities).

- Department of Health should provide funding for the Healthy Child, Healthy Future; Child Health Promotion Programme to increase compliance with the regional immunisation schedule through local community practitioner and health visitor services (or other community-based services), to improve access to immunisation information and provision.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Explore ‘Vaccines in Practice’ eLearning, which has been developed by the RCPCH and mapped to the GP curriculum. It aims to develop trainees’ skills in communicating the benefits of vaccines and is available online.22 Immunisation eLearning is also available online from eLearning for Healthcare.23

- Making every contact count. Practitioners should take every opportunity to enquire about vaccination history, and to counsel families and carers, or young people, of the importance of vaccination. Practitioners should direct them to immunisation services for routine or catch-up immunisations, particularly for children and young people at risk of low vaccine uptake. Where possible, vaccinations should be offered during consultations. Where this is not possible, there should be clear communication to document the need for vaccination.

- Address concerns over immunisations. Parents and/or carers, and young people themselves when it comes to vaccinations in adolescence, should be offered the opportunity to discuss their concerns. Professionals should sensitively but directly address any concerns about the safety and efficacy of routine immunisations.24

- Guidance for professionals on communicating with parents and/or carers on vaccines is available from: NICE,25 UK Health Security Agency,26 and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.27

- Parents and/or carers can be signposted to further sources of information, such as the NHS28 and the Oxford Vaccine Knowledge project.29

- Dispel common misconceptions over contraindications to vaccination. Egg allergy is commonly considered to contraindicate the MMR vaccination, but this is no longer correct (see advice on Measles from UK Health Security Agency Green Book).30 When seeing children and young people with allergies, it should be made clear that allergies rarely interfere with vaccines.

- Role-modelling. Health professionals should ensure that they themselves are vaccinated in line with guidance provided by UK Health Security Agency and the other public health agencies across the UK.

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Vicki Osmond, RCPCH Policy & External Affairs Division

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

World Health Organisation. 2019. Immunization coverage fact sheet. Available from: WHO

UK Health Security Agency. 2022. The hexavalent DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB combination vaccine. London: UK Health Security Agency.

NHS. 2019. Routine Immunisations from Autumn 2019

UK Health Security Agency. 2013. Immunity and how vaccines work: the green book, chapter 1. Available from: GOV.UK

Public Health England. 2018. Making Measles History Together: A resource for Local Government.

Kmietowicz, Z. 2018. Measles: Europe sees record number of cases and 37 deaths so far this year. British Medical Journal.

World Health Organisation. 1999. Health 21: The health for all policy framework from the WHO European region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Public Health England. 2018. Cover of vaccination evaluated rapidly (COVER) programme 2018 to 2019: quarterly data. Available from: GOV.UK

Public Health Wales. Data unavailable. Immunisation and vaccines. Available from: NHS Wales

Public Health Agency NI. Date unavailable. Vaccination coverage. Available from: Public Health Agency NI.

Information Services Division Scotland. Date unavailable. Immunisation: Child Health. Available from: IDS Scotland.

World Health Organisation. 2013. Global vaccine action plan 2011-2020. Geneva: 2013.

Information Services Division Scotland. 2018. Childhood Immunisation Statistics Scotland: Annual uptake rates by deprivation.

Public Health Wales. 2018. Inequalities in uptake of routine childhood immunisations in Wales: 2017-18.

Forster, A.S. et al. 2016. Ethnicity-specific factors influencing childhood immunisation decisions among Black and Asian Minority Ethnic groups in the UK: A systematic review of qualitative research. Journal Epidemiology Community Health.

Samad, L. et al. 2006. Differences in risk factors for partial and no immunisation in the first year of life: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). 2009. Immunisations: Reducing differences in uptake in under 19s. Available from: NICE.

Riches, A. et al. 2019. Interventions to improve engagement with immunisation programmes in selected underserved populations. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland.

Letley, L. & Yarwood, J. 2018. Changing attitudes to childhood immunisations in English parents, British Journal of General Practice.

Forster, A.S. et al. 2016. A qualitative systematic review of factors influencing parents’ vaccination decision-making in the United Kingdom. SSM – Population Health.

Royal Society for Public Health. 2019. Moving the needle: Promoting vaccination uptake across the life course. Royal Society for Public Health.

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Date unavailable. Vaccines in practice – online learning. Available from: RCPCH.

Health Education England. Date unavailable. E-Learning for Healthcare: Immunisation. Available online: e-LFH.ORG.

Bedford, H., Elliman, D. 2019. Fifteen-minute consultation: Vaccine-hesitant parents. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Education and Practice.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2017. Immunisations: reducing differences in uptake in under 19s: Public health guideline [PH21]. Available from: NICE.ORG.UK.

UK Health Security Agency. 2022. Collection: Immunisation. Available from: GOV.UK.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Let’s talk about protection: Enhancing childhood vaccination uptake. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

NHS. Date unavailable. Vaccinations. Available from: NHS.UK.

University of Oxford. Date unavailable. Vaccine Knowledge Project. Available from: http://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/

UK Health Security Agency. 2019. Measles: the green book, chapter 21. Available from: GOV.UK.