Suicide

The rate of young people ending their own life has increased across the UK, with trends considerably higher for young men than young women aged 20-24.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- Suicide one of the leading causes of death in children and young people.

- Suicide may be linked to many factors, including: poor mental health; self-harm; academic pressures or worries; bullying; social isolation; family environment and bereavement; relationship problems; substance misuse; or neglect. Risk factors are cumulative over the life course, and adverse childhood experiences, deprivation, and poor physical health also contribute to the risk.

- Suicide represents the extreme endpoint of mental ill-health in children and young people. Many more young people either have suicidal ideation, attempt suicide, and a greater number still self-harm.

- Official records of deaths by suicide may underestimate true numbers of deaths where suicidal intent was present, due to the high burden of proof that coroners require to determine official cause of death. However, in 2018, in England and Wales the standard of proof used by coroners to determine whether a death was caused by suicide was lowered to the “civil standard” (i.e “balance of probabilities” where previously it had been “beyond reasonable doubt”), and is likely to affect official records (Scotland and Northern Ireland are not affected).1

Many young people don’t understand what mental health is and shy away from talking about any issues they may have.

Key findings

- Over the past 15 years, the UK rate of suicide among 15-24 year olds has gradually fallen, but rose again in 2018 – although this be partly due to a change in coronial standards rather than a true rise. Between 1992 and 2017, the UK rate of suicide per 100,000 young people aged 15-24, decreased from 10.7 to 7.3, but rose to 9.1 in 2018 – a total of 714 registered deaths.

- Across the UK, the suicide rate is highest within Northern Ireland, at 17.8 per 100,000 young people aged 15-24 in 2018; England was the lowest at 8.1.

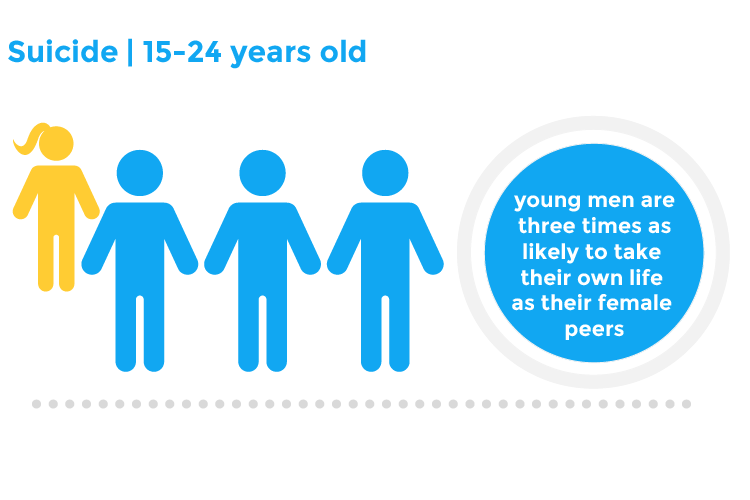

- In all age categories for children and young people, young men are more likely to take their own lives than young women. Between the ages 15-24 in the UK, male suicides were three times more common than female suicides (ONS total of 532 total male suicides, compared to 182 total female suicides in 2018).

- Since 2013, suicide rates have also risen among younger males aged 10-14, and among females across all ages.

- In England, a quarter of 11-16 year olds, and nearly half of 17-19 year olds (46.8%), with a mental disorder reported that they have self-harmed or attempted suicide at some point in their lives. For 11-16 year olds, this represents a greater than eightfold risk compared to those without a mental health problem (25.5% compared to 3.0).2

- In 2018/19, in 30% of counselling sessions provided by Childline (NSPCC) the primary concern was identified as mental / emotional health. Since 2009/10, there has been a sharp increase in the total number of referrals Childline counsellors have made to external agencies where there have been suicidal concerns – with a total of 3,518 referrals made in 2018/19.

Rates calculated using the number of deaths due to suicide. If population numbers were not provided, these were obtained using mid-year estimates from the Office of National Statistics.3

Rates calculated using the number of deaths due to suicide. If population numbers were not provided, these were obtained using mid-year estimates from the Office of National Statistics.3

What does good look like?

Increased investment in improving the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people. There is significant variation in the funding of mental health provision for children and young people, which is shared between NHS and local authorities.4 Crucial to suicide prevention is universal, equitable access to mental health services across the whole population, with a targeted focus on improving services for young people across education, social care, youth justice and health

Reduced stigma of seeking health for mental health problems. There should be targeted mental health support mechanisms for vulnerable groups (eg young men), to provide tailored support to those who may feel uncomfortable accessing mental health services.

Improved early identification of mental health problems across primary and community services. Early identification of mental health difficulties should be established as a core capacity of all education, youth justice and social care professionals who work with children – as well as health professionals in primary care and the community. This will require major investment into training and workforce development.

Better support for those who are affected by suicide. There are generally at least 6 close friends or family who are directly affected by each death by suicide – and many others who are affected such as fellow pupils or social acquaintances, not to mention emergency first responders and healthcare professionals.5 There is a need for universal support and increased vigilance in the aftermath of any suicide, which should be delivered across health, education or social care sectors.

Policy recommendations

- Department of Health and Social Care and Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, Every Mind Matters campaign should be supported and regularly reviewed. UK Government should provide funding for future delivery of this campaign through print and digital media and should target the general population.

- We welcome Scottish Government’s ‘Suicide Prevention Action Plan: Every Life Matters’. Scottish Government should commit to providing 24/7 crisis support services specifically for children and young people as recommended by the National Suicide Prevention Leadership Group.

- The Together 4 Children and Young People programme and the Ministerial Group delivering the recommendations made in the Mind Over Matter’ (2018) report, provide structures to improve children and young people’s mental health services. We welcome continued funding for Together 4 Children and Young People which should continue beyond 2021. In particular, we welcome commitments to work with Regional Partnership Boards to understand current provision and enhance early help and support; and to implement the Neurodevelopmental (ND) pathway and standards developed during the first phase, working coherently to deliver ALN Act provisions and an enhanced response for children and young people with ND.

- Welsh Government should resource and support these programmes to ensure delivery of a whole system approach and support the ‘missing middle’ who need services but do not meet the criteria for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS)services. This system should incorporate education and a Whole School Approach, early intervention, community based support and targeted support for vulnerable groups.

- The Public Health Agency should deliver a public health messaging campaign aimed at reducing stigma among children and young people around seeking help and support for mental health concerns, such as the Change Your Mind campaign.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Early recognition and appropriate mental health support & follow up, especially for young people presenting with indications of self-harm. Health professionals should take advantage of every encounter to enquire about mental wellbeing, recognise early signs of poor mental health and be alert to potential disclosures (verbal and non-verbal) from children and young people. They should signpost, advocate for access to, or directly refer children and young people to, appropriate mental health services to support their needs.

- Young people who have been recently bereaved, and in particular if that bereavement came about as a result of suicide, are at significantly higher risk of suicide themselves6 and therefore require extra vigilance and a lower threshold for mental health support and early intervention.

- Resources:

- NSPCC’s Suicide: learning from case reviews provides information for professionals on how to listen and engage with young people with suicidal thoughts and how to work with agencies to manage mental health problems.7

- Education Wales have published practical guidance specifically in prevention of suicide and self-harm (Responding to issues of self-harm and thoughts of suicide in young people) which is aimed at teachers but relevant for all child health professionals.8

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Zara Schneider, RCPCH Research & Quality Improvement Division

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

ONS (2019). Suicides in the UK: 2018 registrations

NHS Digital (2018) Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017.

Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Mid-2001 to mid-2018 detailed time-series. June 2019.

Children’s Commissioner (2019) Early Access to Mental Health Support.

Young I et al. (2012) Suicide bereavement and complicated grief Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 14(2): 177–186

Pitman AL, Osborn DPJ, Rantell K, et al Bereavement by suicide as a risk factor for suicide attempt: a cross-sectional national UK-wide study of 3432 young bereaved adults BMJ Open 2016; 6:e009948. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009948

NSPCC (2014). Suicide: learning from case reviews.