Accidental injury

Non-intentional injuries are a leading cause of death and disability in young children, especially from falls, poisonings and drowning. Improved home safety is needed to prevent injuries.

This indicator was published in March 2020.

In May 2021 we updated our graphs and charts where new data had been published, and we reviewed our policy recommendations by nation.

Background

- Non-intentional injuries in children are a public health concern and are a leading cause of death and disability, especially among young children.

- Major mechanisms of non-intentional injury include poisoning, falls, drowning and thermal injuries.1 (Road traffic accidents are excluded from this indicator and are explored separately in this indicator.)

- Non-intentional injuries are related to socioeconomic deprivation. Children and young people from the most deprived areas in England experience 40% more admissions for nonintentional injury than those in the least deprived.2

- Most non-intentional injuries are preventable through national and local action. Aside from causing morbidity and mortality for children, there are cost implications for health services, local authorities and families.3

We need stay-safe training.

Key findings

- Trends have fluctuated slightly from 2012/13 to 2018/19, though generally remain stable.

- In 2018/19 there were 45,661 hospital admissions due to non-intentional injuries in children under 5 years in England and Wales.

- The rates from 2018/19 in Wales are the lowest they have been in eight years, 16.1 per 1,000 – though Welsh rates continue to be higher than the other nations, in comparison to 12.8 per 1,000 in England in 2018/19 and 10.7 per 1,000 in Scotland in 2017/18.

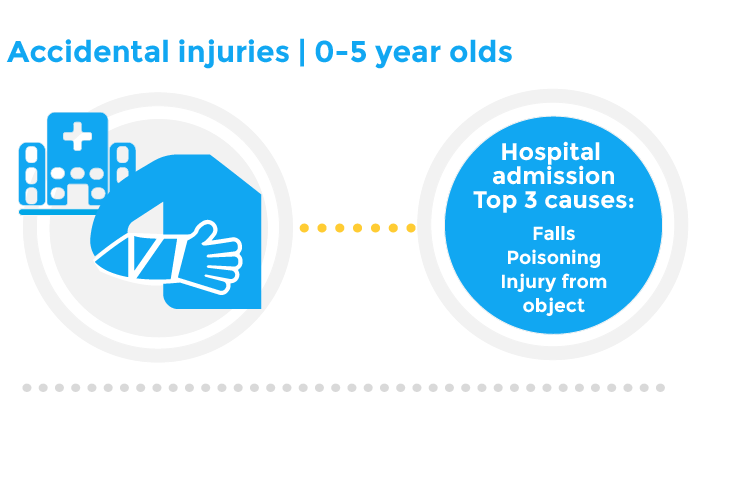

- The top causes of non-intentional injuries vary within the UK four nations, but include: falls, poisoning, and injuries relating to objects. (Note that this indicator excludes hospital admissions due to road transport injury.)

- No directly comparable recent data for Northern Ireland were publicly available. The latest available data in 2014/15 for children aged 0-9 years show a hospital admission rate of 3 per 1,000.

Rates calculated using mid-year population estimates from the Office of National Statistics.4

The standardised discharge ratio is equal to the number of observed discharges divided by the number of expected discharges, times 100, where the number of observed discharges is defined as the number of discharges in each area of interest (e.g. deprivation quantile), and the number of expected discharges is defined as the number of discharges that would have been ‘expected’ in the area of interest if the Scottish discharge rates had prevailed. Note that a value of 100 represents the value across the population as a whole.

What does good look like?

Data collection across all four nations. Health & Social Care in Northern Ireland should come in line with the other four nations and regularly publish data on this important public health indicator.

Educate and empower children, young people and families on safety issues. Data shows that many accidental injuries occur within the child’s home. Improved and targeted education will enable families to recognise potential risks within their environment and to potentially prevent accidents.

Provide a safe home environment for children and young people. Injury prevention is everyone’s business, requiring multi-agency collaboration across a range of sectors (health, education, fire safety, leisure, housing, and town planning). Home safety assessments, and the provision of safety equipment where needed, is important. New-build housing should be designed with child safety principles in mind.5

Make the built environment safe for children and young people. Outside the home, safe built environments promote healthy lifestyles by providing children and young people with places to exercise and play, encouraging wider public health improvements (see indicator on healthy weight).

Address health inequalities. Data shows that accidental injuries disproportionately affect families in deprived areas. More deprived families may have less access to safety equipment, and families may have less access to safety education and less capacity to supervise or change children’s unsafe behaviours. Additionally, the built environment itself may have more environmental hazards than in more affluent areas. Safety education and the provision of safety equipment should be provided to those at most risk.

Policy recommendations

- UK Government should resource Local Authorities to implement in full NICE public health guideline [PH30] ‘Unintentional injuries in the home: interventions for under 15s’. We support Public Health England’s recommendation to implement home safety assessments particularly to families living in deprived areas or social housing, combining assessment, advice and provision of safety equipment (as covered in NICE PH30).

- We support recommendations for children and young people outlined by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) within their national strategy for accident prevention in England. Recommendations from the strategy should be implemented in full. The strategy provides recommendations on:

- Addressing health inequalities;

- Improving data collection;

- Providing safer environments;

- Improving product safety;

- Ensuring a systematic approach and leadership to tackle injury prevention;

- Providing education and training;

- Expanding the research and evidence-base on the reasons for accidental injuries among young people.

- Local Authorities should implement in full NICE public health guideline [PH30] ‘Unintentional injuries in the home: interventions for under 15s’.

- We welcome the launch of Scottish Government’s online hub for local level practitioners working with communities to deliver targeted safety messages and initiatives to prevent accidental injuries. This should be routinely reviewed and updated with new evidence and exemplars.

- Scottish Government should work with the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) to develop a national strategy for accident prevention in Scotland.

- Local Authorities should implement in full NICE public health guideline [PH30] ‘Unintentional injuries in the home: interventions for under 15s’.

- Welsh Government should work with the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) to develop a national strategy for accident prevention in Wales.

- We welcome Northern Ireland’s ‘Home Accident Prevention Strategy’ (2015-2025), which focuses on children under the age of five as a priority group. The Department of Health should implement the strategy in full and provide regular reporting on the progress of implementation. Implementation of the strategy will deliver the following stated aims to:

- Empower people to better understand the risks and make safe choices to ensure a safe home with negligible risk of unintentional injury.

- Promote safer home environments.

- Promote and facilitate effective training, skills and knowledge in home accident prevention across all relevant organisations and groups.

- Improve the evidence base.

- The Department of Health should implement in full NICE public health guideline [PH30] ‘Unintentional injuries in the home: interventions for under 15s’.

What can health professionals do about this?

- Promote the prevention message. Accident prevention information and advice should be displayed in public areas of any setting in which children and young people, families or expectant mothers might be in attendance.

- Make every contact count and signpost families to local accident prevention services, such as for home safety assessments and safety equipment, where appropriate.

- Recognise the impact of social determinants of health and support families in need. Due to the increased risk of non-intentional injury among children and young people living in deprived areas, and especially those in poor quality housing, practitioners should advocate for families so that they are able to secure good quality housing. This is especially important for those in temporary homeless accommodation, where risk for unintentional injury should be identified.

- Sources of further information:

- Clinical guidance is available from NICE regarding unintentional injuries, describing prevention strategies for under 15s.6

- Children in Wales and Public Health Wales have developed the Keep Kids Safe programme, covering 12 key injury and poisoning risk areas in the home. It is suitable for use by all health professionals, containing relevant guidance for primary and secondary care and community health teams.7

- The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents published a national strategy for accident prevention in 2018, which aimed to be a call to action for reform in the delivery of accident prevention across England.5

Contributing authors

- Dr Ronny Cheung, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Lead

- Rachael McKeown, RCPCH State of Child Health Project Manager

- Kirsten Olson, RCPCH Policy & External Affairs Division

- Dr Rakhee Shah, RCPCH State of Child Health Clinical Advisor

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020) State of Child Health. London: RCPCH. [Available at: stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk]

References

World Health Organization Europe. 2008. European Report on Child Injury Prevention. Denmark: World Health Organization.

Public Health England. 2019. Health matters: Prevention – a life course approach. Available from: PHE

Public Health England. 2018. Reducing unintentional injuries in and around the home among children under five years. London: Public Health England.

Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Mid-2001 to mid-2018 detailed time-series. June 2019.

Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents. 2019. Safer by design: A framework to reduce serious accidental injury in new-build homes.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2010. Unintentional injuries: prevention strategies for under 15s: Public health guideline [PH29]. Available from: NICE

Children in Wales. Date unavailable. Keep Kids Safe 2017. Available from: Children in Wales